By Daniel Aronowitz

The Miller Shah law firm has filed nine fiduciary malpractice lawsuits to date against some of the lowest-fee, best-managed defined contribution plans in America. After years of higher-fee plans with actively managed investment options facing imprudence challenges, this next chapter in the long war against large-plan fiduciaries represents a cynical and meritless attack against low-fee plans that must be dismissed as implausible under the federal pleading standard. These cases allege that it is imprudent to choose and maintain BlackRock low-fee index target-date funds (TDFs) that have the highest Morningstar rating and TDF ranking in the entire market because they purportedly underperformed compared to other popular target-date funds. Aside from the fact that the underperformance claims are factually wrong, these cases are implausible because (1) they fail to allege a meaningful benchmark with similar investment objectives and strategies from which to plausibly allege that the highly-rated BlackRock funds have underperformed; and (2) the alleged underperformance amount is not plausible – even if truthfully pled – because BlackRock TDFs have not suffered sufficiently dismal performance over a long-term time period against any measure. To the contrary, the BlackRock funds are designed to provide – and have provided – good investment performance in advancing markets and downside protection in declining markets. These lawsuits are manufactured imprudence claims designed to profit off the high risk and cost of defending high-stakes litigation, but that is exactly why faithful application of the pleading standard is crucial to protect fiduciaries who have done nothing wrong in their service to plan participants.

A New Chapter in Excessive Fee Litigation

The initial lawsuits alleging excessive plan fees under ERISA were filed from 2006 to 2015 against large corporate plans. These cases involved a ten-year saga in which the Schlichter law firm innovated a new type of fiduciary imprudence claim against large-plan fiduciaries. The core claim was the large plans had failed to leverage their size to negotiate lower fees from investment and other plan service providers. These initial cases demonstrated that courts will largely view excessive fees claims as potentially legitimate imprudence claims, culminating in the 2015 Supreme Court’s decision in Tibble v. Edison that plan fiduciaries have an ongoing duty to monitor plan investments.

The second wave of cases of excessive fee and imprudent investment litigation was filed against twenty university plans in 2016-17 for allowing excessive plan fees. Led again by the Schlichter law firm, these cases alleged that university plans with multiple recordkeepers and large investment menus failed to leverage the bargaining power of the large asset size of the plan to lower plan administration costs, maintained uncapped revenue sharing that overpaid plan providers, and offered confusing slates of investment options that often contained higher retail share-class fees which were inappropriate for large plans that could negotiate lower fees. These cases often contained the claim that certain actively managed investment options failed to justify the higher fees in terms of relative investment performance compared to the alternative choice of lower-fee index funds, which often outperformed active funds. These university cases raised certain legitimate issues, particularly with respect to retail-share class investments, that plan fiduciaries were failing to exercise the best possible fiduciary practices in making proactive fiduciary decisions. Most of the current case law interpreting the pleading standard to properly allege ERISA claims of fiduciary imprudence has been interpreted under these problematic fact patterns, including the Supreme Court’s decision in Hughes v. Northwestern.

The third wave of excessive fee lawsuits was filed against actively managed Fidelity Freedom and other target-date funds like Wells Fargo and Northern Trust. These lawsuits focused on claims of investment underperformance, mostly based on the claim that the higher cost of actively-managed investments failed to compensate for the additional investment expense required for active management. Many of these lawsuits also had problematic additional claims that Fidelity and other investment managers charged higher retail-share class investment fees that were inappropriate for large plans. The crux of these claims was that it is imprudent to offer active investment options. The results of decisions deciding whether the third wave of cases are plausible under the pleading standard have varied, with some cases dismissed, and others allowed to proceed to discovery and ultimate settlement.

We have now entered a new, fourth chapter in excessive fee litigation with lawsuits attacking fiduciaries who chose BlackRock investments for their low fees, but allegedly ignored investment performance. To the extent that the first three waves of excessive fee cases had potential merit that plan fiduciaries failed to act prudently in certain circumstances, including failing to leverage plan size for lower fees, the BlackRock claims do not. Except for two of the cases that allege excessive recordkeeping fees, these cases do not allege excessive investment fees, because BlackRock funds are offered at eight or nine bps – less than 80% of the cost of the actively managed TDFs to which the BlackRock investments are being compared. In fact, most of the nine plans being sued have all-in plan fees, including both plan administration and investment fees, of .11-.15%. The fees in these plans are among the lowest of all plans in the entire country. Of the 750,000+ American defined contribution retirement plans, the nine plans being sued are among the top fifty plans in the country in terms of lowest all-in fees. For perspective, a plan with all-in fees of 11 basis points has 75-80% lower fees than plans with active T. Rowe Price, American Funds or Fidelity Freedom target-date funds as the QDIA, which have all-in plan fees of 40-50 bps+, and sometimes significantly higher. Whereas the prior waves of excessive fee cases alleged that it was imprudent to offer funds with the high fees of active funds, the same lawyers are now alleging that is now somehow imprudent to offer funds with low fees. Damned if you do, and damned if you don’t.

Instead of alleging excessive fees, these lawsuits are, for the most part, pure investment underperformance cases. The new lawsuits filed by Miller Shah allege that it is now “in vogue” to chase high fees but ignore investment performance. The claims are essentially that BlackRock funds are a deficient product that are inappropriate for institutional plans managed by fiduciaries. These cases attempt to allege that plan fiduciaries were imprudent in choosing low-fee BlackRock funds because they had lower investment performance than the five other most popular target-date series available in the market offered by American Funds, T. Rowe Price, Vanguard, and Fidelity Freedom (active and index TDF series). Whereas the initial cases alleged that plan processes were deficient for failure to conduct benchmarking or requests-for-proposals for lower fees, there is nothing alleged about the plan processes of the plans being sued. That is because each of these plans likely had the investment advice and monitoring of investment performance by the best investment advisors in the country, all of which legitimately advised that the BlackRock funds were an appropriate choice to fund the retirement of the plan participants of these great companies.

The Pleading Standard for Investment Underperformance Cases

As we have pointed out previously, as recently as March 14, 2022, Morningstar reviewed the BlackRock LifePath Index Target-Date series and concluded that it “remains a first-class target-date series.” Morningstar has rated the BlackRock TDFs as the number one target-date option out of 143 total options for multiple years running, including in the most recent 2022 target-date landscape report. So how is a plaintiff law firm allowed to allege that the highest-rated target-date funds available in the market somehow represent fiduciary malpractice and require plan fiduciaries to pay millions of dollars to defend the claims, and even more millions of dollars to settle the cases? The reason is that nothing in the American judicial system prevents outrageous claims from being filed. But that is why the pleading standard is so important. It is up to judges to apply the pleading standard to separate the “sheep from the goats” in dismissing meritless cases. In an example of which we are all familiar, dozens of cases were filed after the 2020 Presidential election claiming that the election was stolen, and courts applied a pleading standard to dismiss the cases when they were based on false speculation and lack of proof. We now have a more well-developed ERISA fiduciary pleading standard that similarly must be applied to unsupported claims that BlackRock TDFs have underperformed to the point of fiduciary malpractice.

The two recent decisions by the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals in CommonSpirit and TriHealth analyze the pleading standard for investment underperformance cases based on Supreme Court guidance from Hughes v. Northwestern, Tibble v. Edison and Fifth Third Bancorp v. Dudenhoeffer. The CommonSpirit and TriHealth cases both involved the claims that Fidelity Freedom and T. Rowe Price active funds were imprudent because they contained high fees and underperformed passive target-date funds that had lower investment management fees. These two cases are representative of several dozen cases targeting plans with Fidelity Freedom funds. Miller Shah filed many of these cases, and argued that the allegedly imprudently target-date funds underperformed other popular target-date funds, including the very same BlackRock funds that are allegedly imprudent in the recently filed cases. For example, in Wehner v. Genentech, Miller Shah alleged that the Genentech plan imprudently selected custom target-date funds that underperformed off-the-shelf BlackRock index and other popular target-date funds. The Sixth Circuit in CommonSpirit held that claims of investment under-performance are not plausible based on simply pointing to a fund with better performance. Instead, plausible claims require a deficient process and signs of serious distress. The CommonSpirit test to plausibly plead underperformance requires (1) comparison to a meaningful benchmark of investments with the same objectives and strategy, and (2) a seriously dismal level of underperformance over the long-term.

The CommonSpirit Court explained that fiduciaries can violate ERISA by imprudently offering specific investment funds. “ERISA, in other words, does not allow fiduciaries merely to offer a broad range of options and call it a day.” Citing to the Supreme Court’s decisions in Tibble v. Edison and Hughes v. Northwestern, the Court ruled that plan fiduciaries must ensure that all fund options remain prudent options. But that does not mean that an unsupported claim of underperformance is plausible as a viable fiduciary imprudence claim under the federal pleading standard. To the contrary, “there is still room for offering an actively managed fund that costs more but may generate greater returns over the long haul. Nor does a showing of imprudence come down to simply pointing to a fund with a better performance.”

The Court explained that it may be necessary to show that another fund in which the plan may have invested performed better, but that “factual allegation is not by itself sufficient.” The Court instead offered that “[i]n addition, these claims require evidence that an investment was imprudent from the moment the administrator selected it, that the investment became imprudent over time, or that the investment was clearly unsuitable for the goals of the fund based on ongoing performance.” But even that is not enough, as the Court said that “merely pointing to a five-year snapshot of the lifespan of a fund that is supposed to grow for fifty years does not plausibly plead an imprudent decision” that breaches a fiduciary duty because it is “largely a process-based inquiry.” (emphasis added). The reason is that “precipitously selling a well-constructed portfolio in response to disappointing short-term losses, as it happens, is one of the surest ways to frustrate the long-term growth of a retirement plan.” “Any other rule would mean that every actively managed fund with below-average results over the most recent five-year period would create a plausible ERISA violation.”

The CommonSpirit court cited the Eighth Circuit’s decisions in Washington University v. Davis and Meiners v. Wells Fargo & Co. that require a comparison to a “meaningful benchmark,” and that underperformance claims cannot be based on purported comparison of two general investment options that “have different aims, different risks, and different potential rewards that cater to different investors. Comparing apples and oranges is not a way to show that one is better or worse than the other.” As the Eighth Circuit held in Meiners v. Wells Fargo, “[t]he fact that one fund with a different investment strategy ultimately performed better does not establish anything about whether the [challenged funds] were an imprudent choice at the outset.”). The CommonSpirit Court explained how performance comparisons between competing funds with different objectives do not “move the claim from possible and conceivable to plausible and cognizable”:

“Just as comparison can be the thief of happiness in life, so it can be the thief of accuracy when it comes to two funds with separate goals and separate risk profiles. That is why disappointing performance by itself does not conclusively point towards deficient decision-making, especially when we account for ‘competing explanations’ and other ‘common sense’ aspects of long-term investments.”

In the Fidelity Freedom cases like CommonSpirit, participants argued that Fidelity Freedom index funds were appropriate comparators to the actively managed Freedom Funds because they are sponsored by the same company, managed by the same team, and use a similar allocation of investment types. But the CommonSpirit Court rejected these claims because each fund has distinct goals and distinct strategies, making them inapt comparators. The explanation by the CommonSpirit Court is worth quoting verbatim:

“Nor is it clear that an after-the-fact performance gap between benchmark comparators by itself violates the process-driven duties imposed on ERISA fund managers. That a fund’s underperformance, as compared to a ‘meaningful benchmark,’ may offer a building block for a claim of imprudence is one thing. Meiners, 898 F.3d at 822. But it is quite another to say that it suffices alone, especially if the different performance rates between the funds may be explained by a ‘different investment strategy.’ Id. at 822–23. A side-by-side comparison of how two funds performed in a narrow window of time, with no consideration of their distinct objectives, will not tell a fiduciary which is the more prudent long-term investment option. A retirement plan acts wisely, not imprudently, when it offers distinct funds to deal with different objectives for different investors.”

Once a plaintiff has established a meaningful benchmark that matches the distinct investment goals and objectives of the disputed investment option, the CommonSpirit Court continued that the second part of the test to prove a sufficient level of underperformance is also process-oriented: “disappointing performance by itself does not conclusively point towards deficient decision-making, especially when we account for ‘competing explanations’ and other ‘common sense’ aspects of long-term investments.” Mere performance comparisons typical of excessive fee lawsuits lack the “proper foresight-over-hindsight perspective.” Indeed, an “after-the-fact performance gap between benchmark comparators” does not violate “the process-driven duties imposed on ERISA fund managers.” So what process-oriented evidence would be needed for a purported excessive fee complaint to move from possible and conceivable to plausible and cognizable as required under the pleading standard? The Court stated that “[w]e would need significantly more serious signs of distress to allow an imprudence claim to proceed.” (emphasis added). The second part of the investment imprudence test is thus long-term signs of serious investment underperformance. Minor variances against a meaningful benchmark does not meet this test.

Importantly, in assessing whether it was prudent for fiduciaries to select and maintain Fidelity Freedom funds for the retirement plan, the CommonSpirit Court was persuaded by the independent analysis of Morningstar, and cited directly to the 2021 Morningstar annual Target-Date Strategy Landscape report. See Jason Kephart & Megan Pacholok, 2021 Target-Date Strategy Landscape, Morningstar 8 (2021), https://www.morningstar.com/research/documents/1028662/2021-target-date-strategy-landscape. The Court noted that “Morningstar gave the Freedom Funds and the Index Funds a “Silver” rating and rated the Freedom Funds’ management team and process as “above average” or better.” As we reviewed in our previous blogpost, Morningstar has perennially rated the BlackRock LifePath target-date funds in the highest Gold category and in the #1 position, rated it as a “first-rate option” for retirement plans – a higher rating than the TDFs at issue in CommonSpirit. This is enough to dismiss the BlackRock cases outright. But as analyzed more fully below, the Miller Shah fiduciary imprudence claims against plans with BlackRock LifePath target-date funds, which lack any attempt to prove a deficient fiduciary process, fails to meet the CommonSpirit two-part process-oriented test of (1) a meaningful benchmark with distinct goals and objectives, and (2) long-term serious signs of distress and underperformance.

The BlackRock Cases Lack a Meaningful Benchmark with the Same Distinct Goals and Objectives

Plaintiffs in all nine cases against plans with BlackRock TDFs know they need to establish a meaningful benchmark. But instead of a benchmark that compares BlackRock TDFs to a custom benchmark with similar and distinct investment objectives and strategy, plaintiffs allege that BlackRock TDFs should be compared to the largest six target-date series offered in the market, which make up seventy-five percent of all TDF assets [with statistics drawn from the 2022 Morningstar TDF landscape report]: Vanguard Target Retirement [$1,190B/36.4% market share]; T. Rowe Price Retirement [$350m/10.7%]; BlackRock LifePath Index [$287B/8.8%]; American Funds Target Date Retirement [$248B/7.6%]; Fidelity Freedom $221B/6.8%]; and Fidelity Freedom Index [$152B/4.6%]. Plaintiffs claim that the five non-BlackRock TDF suites “represent an ideal group for comparison” – not because they match the investment goals and strategy of plan fiduciaries – but because “they represent the most likely alternatives from which to replace the BlackRock index TDFs.” In sum, plaintiffs are taking the position that investment mix and strategy is irrelevant. Instead, they claim that BlackRock TDFs need to be compared against other popular target-date funds from Vanguard, American Funds and T. Rowe Price, never mind that only two of these TDFs are passively managed.

Plaintiffs are thus claiming that the appropriate benchmark from which to allege to fiduciary imprudence is (1) three active TDFs – American Funds, T. Rowe Price, and Fidelity Freedom; and (2) two index TDFs offered by Fidelity Freedom and Vanguard. This obviously fails the Sixth Circuit CommonSpirit and Eighth Circuit Meiners test of a meaningful benchmark with the same distinct investment objectives. Plaintiff do not even attempt to allege the actual investment objectives of any of the nine plans. Nor do they even attempt to articulate what types of investments make up the BlackRock TDFs compared to the purported comparator plans. That is why the imprudence claims are implausible under the federal pleading standard.

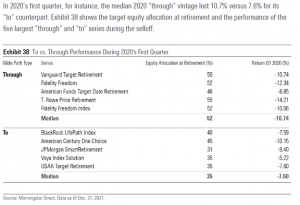

At the outset, all of five of these alternative TDF series are “through retirement” TDFs as opposed to the different “to retirement” TDF strategy offered by the BlackRock Funds. Consequently, the “to” retirement BlackRock TDFs are being improperly compared to more aggressive “through” retirement TDF suites with higher equity allocations closer to retirement. As we demonstrated in our prior blogpost written right after the first two lawsuits, the nine lawsuits filed to date by Miller Shah represent a wholesale attack on any TDF that utilizes the more conservative “to” retirement glidepath. The key difference in the BlackRock LifePath glide path is that it is a “to” retirement glidepath which is designed for an investor who expects to invest in the fund up until retirement, whereas a “through” glide path is for the investor who plans to withdraw funds gradually after retirement. Of the top six most popular TDFs in the market, BlackRock is the only option with the more conservative “to” retirement glidepath designed for investments to be transferred out of the plan at retirement. You cannot compare “to” retirement glidepaths against “through” glidepaths.” The reason is that a considerably heavier weight to equities in a through-retirement TDF strategy closer to retirement will likely produce greater returns in up markets. But the opposite is true in down markets.

Miller Shah labels the BlackRock “to” retirement TDF strategy a “vastly inferior retirement solution” that have “consistently and dramatically underperformed” other TDF offerings. But Morningstar’s analysis shows that the BlackRock “to” retirement strategy is a superior solution in down markets:

The Morningstar analysis also shows that the BlackRock funds perform better than most of the most popular “to” retirement TDF series. Again, the Miller Shah complaints with charts and graphs appear very authoritative, but the claims of underperformance are just plain false and represent inappropriate comparisons of funds with different investment strategies and objectives.

Second, the BlackRock lawsuits attempt to compare the performance of active target-date funds like T. Rowe Price, American Funds and Fidelity Freedom to the BlackRock passively managed TDFs. There have been many cases analyzing whether it is appropriate to compare active target-date funds to index target-date funds. But these new complaints turn this on a head and purport to compare index returns to active returns. The obvious rebuttal is that active target funds are supposed to have superior returns. They are supposed to have a higher rate of return in the long-run because they employ active strategies to try to outperform the market, and that is how they justify their higher fees. They seek higher return by taking a higher investment risk.

Compared to golf, it is like the decision to hit your driver or your three-wood off the tee. For me, I can hit the driver 200+ yards, but I am less accurate and will miss the fairway more often, and put bogey or higher into play. But sometimes I pull out my three-wood as a more conservative choice. I can only hit my three-wood about 185 yards, but my accuracy is higher, and I have a better chance of hitting the fairway. I have better odds of making par or birdie if I get closer to the green with the driver, but it sometimes makes sense to play it safe and hit the more accurate three wood. Active funds cannot be compared to passive funds; and passive fund returns cannot be compared to active fund returns. The goals and risk-reward calculation and strategy are not the same. The comparisons to the top-performing T. Rowe Price (90 percentile) and American Funds (98 percentile) are particularly inappropriate because both of these funds took extra risk by maintaining a higher equity allocation in their glidepath. That risk paid off in a ten-year bull market, but it is not a sign of fiduciary imprudence to choose a more conservative glidepath from BlackRock. Choosing T. Rowe Price and American Funds is like choosing the driver to achieve investment returns, whereas choosing BlackRock is like pulling out the three wood to ensure consistent performance in up and down markets. Both are legitimate investment strategies and cannot be fairly compared.

The Restatement (Third) of Trusts: We note that the only somewhat persuasive justification for comparing active funds to index funds – and theoretically this could be applied to comparing index funds to active funds – is the obscure reference in the Brotherston v. Putnam case by the First Circuit to section 100 of the Restatement (Third) of Trusts at the end of comment b(1). The Court cites to the partial phrase that the projected returns on investments to determine the amount of loss may be based on “return rates of one or more suitable common trust funds, or suitable mutual funds or market indexes (with such adjustments as may be appropriate).” But any reliance on this section of the Restatement is inappropriate proof-texting that fails to decipher the whole intended meaning. Here is the complete Restatement paragraph:

“Depending on the type of trustee and the nature of the breach involved, the availability of relevant data, and other facts and circumstances of the case, the projected returns on indefinite hypothetical investments during the surcharge period may appropriately be based, inter alia, on: the return experience (positive or negative) for other investments, or suitable portions of other investments, of the trust in question; average return rates of portfolios, or suitable parts of portfolios, of a representative selection of other trusts having comparable objectives and circumstances; or return rates of one or more suitable common trust funds, or suitable index mutual funds or market indexes (which such adjustments as may be appropriate).” (emphasis added).

Plaintiffs relying on the Restatement of Trusts to compare active and index funds are leaving out the crucial modifier “suitable” to market index funds. But more importantly, any use of the Restatement must cite to the second-to-last phrase that provides a basis for calculating loss by comparing to average return rates of “a representative selection of other trusts having comparable objectives and circumstances.” This is the same requirement of the Sixth and Eighth Circuits to prove investment performance. The only valid comparisons are between investments with the same investment objectives.

Third, plaintiffs are purporting to compare BlackRock TDFs to the Vanguard and Fidelity Freedom index TDF offerings – not because they have the same glidepaths and investment strategies or even the same exact investment allocations, but because they are two other popular TDF series recommended by many investment advisors. This does not meet the CommonSpirit and Meiners v. Wells Fargo test because it is not a meaningful benchmark that compares funds with the same distinct investment objectives and strategies. As noted above, the first fatal flaw is that the BlackRock TDFs are “to” retirement TDFs. Plan fiduciaries and their investment advisors select BlackRock TDF precisely because they are designed to be more conservative than the “through” retirement offerings of Vanguard and Fidelity index TDFs. Fiduciaries chose BlackRock to hedge against downside risk in down markets. In addition, the BlackRock glidepaths are different than Vanguard and Fidelity. Vanguard often promotes that it offers a purer strategy without allocations to commodities and real estate. The point is BlackRock has more downside inflation and market hedges that make it a different investment strategy than Vanguard and Fidelity. And as we showed in our last blogpost on these lawsuits, BlackRock has underperformed Vanguard in rising markets, but it is now outperforming Vanguard in the current declining market. Choosing Vanguard is no more prudent or imprudent than choosing BlackRock TDFs, and vice-versa. They represent different investment objectives and goals. The comparisons to other index funds with different investment objectives fail to meet the plausibility standard when they fail to compare funds with the same distinct investment aims and goals.

The BlackRock Cases Fail to Allege Long-Term “Serious Signs of Distress”

While the nine lawsuits would lead you to believe that the BlackRock funds have experienced terrible performance – including claims that the BlackRock TDFs have “consistently and dramatically” underperformed other available TDFs – the hyperbolic claims of investment underperformance are completely fabricated. The most recent performance report on the Morningstar website (see here LIBKX – BlackRock LifePath® Index 2025 K Fund Stock Price | Morningstar) proves that plaintiffs’ underperformance claims have no merit. We quote the Morningstar performance report:

“This series has generally posted strong absolute and risk-adjusted results since its 2011 launch. Over the five-year period through December 2021, the funds’ K share class outpaced 73% of peers on average. The retirement income vintage, which has a stable 40% equity allocation, fared the best. It topped 93% of peers over the period. Notably, all vintages also outpaced their representative S&P Target Date Index benchmarks.”

Just so it is clear, plaintiffs claim consistent and dramatic underperformance by the BlackRock funds, but Morningstar – a nationally renowned investment expert – says that BlackRock LifePath funds chosen by the nine plans have “strong absolute and risk-adjusted results” since inception. The CommonSpirit Court used the same Morningstar report to deny underperformance claims against Fidelity Freedom funds. This Morningstar evidence of positive performance of the higher-rated BlackRock funds is even stronger. In fact, it is so dispositive that all nine courts should be considering rule 11 sanctions for ambushing nine large companies with false claims of fiduciary malpractice.

By contrast, Morningstar rates the performance of the Vanguard target-date offerings that plaintiffs claim is a superior alternative choice as only “above-average” and “middling” in recent markets (VTHRX – Vanguard Target Retirement 2030 Fund Fund Stock Price | Morningstar): “This series of target-date funds has delivered above-average returns over the long term. The funds in the series topped roughly 70% of peers, on average, over the trailing 10 years through January 2022. More recent results have been middling, however, as the series’ overweight to international stocks relative to peers has largely been a headwind.”[i]

These Morningstar references demonstrate that the charts in the plaintiffs’ complaints are not reliable. We believe that they will be disproven in any trial as factually inaccurate. It is not even clear where plaintiffs got their performance numbers, and they do not pretend to validate their numbers with any citations. But even if a court has to assume that they are accurate for purposes of a motion to dismiss, they still do not represent proof of long-term, dismal performance to satisfy the second prong of the CommonSpirit investment underperformance plausibility test. The complaints contain numerous charts comparing the BlackRock performance on a three- and five-year basis to the “peer” group of the five other popular funds. But as noted above, this is a not a fair comparison because the BlackRock TDFs have a distinct and more conservative investment glidepath than all other five TDFs. And the performance differential as alleged in the complaints – even assuming it is true – is approximately .5-2.0% during the three- and five-year time period. There is nothing in the three- and five-year performance charts that constitutes long-term dismal performance or signs of distress.

To the contrary, the performance differentials are minor, and easily explained by the distinct investment strategies and objectives. The complaints do not compare BlackRock funds to the comparator used by BlackRock with the same investment objectives, or even through-retirement index TDFs in which BlackRock funds have performed favorably. The complaints further fail to compare funds with the same mix of investments. The key differentiator of index target-date funds is the percentage allocated to a bond index (as interest rates have gone up dramatically in the last year, lowering bond returns); how much is allocated to international exposure (BlackRock has a 13.28 percent allocation to an international ETF); and how much is allocated to real estate index funds (2.15% for BlackRock, but not in Vanguard TDFs). Some TDFs include a commodity exposure, and others do not. The investment strategies matter because, for example, as noted by Morningstar in the Vanguard performance analysis, international funds have underperformed in recent years, and any TDF with a higher international allocation will have been outperformed by a fund with a higher U.S. allocation given the relative outperformance of U.S. equities – none of which could have been predicated by any market analyst. The same with bonds: a higher exposure to bonds in the last year will lead to a lower return as interest rates skyrocketed. None of this is evidence of fiduciary imprudence to select these funds and distinct strategies. Rather, it is just a difference in investment strategy. But plaintiffs in these lawsuits do not mention any of the actual investment allocation differences between the BlackRock and other popular “peer” funds, except a minor reference to the amount of stock in the glidepath.

BlackRock needs to step forward and demonstrate how its funds have compared to a proper benchmark, but the bottom line is that the comparisons in the complaint do not meet the necessary requirement of serious underperformance required to meet the ERISA pleading standard.

The Euclid Perspective

It costs millions of dollars to defend this type of fiduciary imprudence lawsuit, and the discovery is asymmetrical, meaning that defendants have to spend more money in litigation expense to defend the respective cases. Miller Shah knows this. It is why a tiny law firm can file nine coordinated cases in nine different courts at the same time against some of America’s largest corporations. Miller Shah also knows that nearly every settlement in the excessive fee saga has been achieved because the litigation risk is so high and each plan has fiduciary insurance. [Note, for example, that the Northwestern case is still most likely being litigated because Northwestern has exhausted its limited insurance protection]. The litigation risk is driven by damage models that are astronomical, as even a purported one percent underperformance differential is worth tens of millions of dollars. The plaintiff law firm is banking on leveraging the litigation uncertainty and pressure from plan fiduciaries to settle out of insurance policy proceeds to make the lawyers go away. They know that it is unlikely that any of the cases will go to trial in which they would have to actually prove that BlackRock funds have underperformed any meaningful benchmark. The point is that it is not really about the merits of the underperformance case. Based on prior excessive fee precedent, Miller Shah unfortunately does not need a strong case, or even a truthful case, to succeed. Instead, it is about marshalling enough deceptive charts and claims to convince a court to allow even one of these cases to proceed past a motion to dismiss.

For these reasons, the pleading standard for ERISA class actions is more important than ever before. Miller Shah wins if even one case gets past a motion to dismiss because there will be huge pressure to settle even if the case has no merit. Most product defect class actions in federal courts are consolidated into one court to ensure efficient litigation and consistent rulings. But these cases are unique in that Miller Shah is alleging that BlackRock TDFs are a defective product, but BlackRock is not a defendant in the cases, and the cases are spread around the country against different large plans and will be decided by different judges. The risk is high that the same claims will reach different results. But unless the plan processes were different – and there is nothing in the complaints about how the plans chose and monitored these investments – it will be unfair to allow different results for the same claims. If the Department of Labor is not going to step in to restore justice to the fiduciary system and advocate for plan fiduciaries who managed some of the best plans in America, then judges have to faithfully apply the federal pleading standard to dismiss these cases that lack sufficient proof of investment underperformance.

[i] Morningstar’s review of Vanguard TDF performance continues in full: “Vanguard was one of the first to move to a strategic international stock allocation that comes close to the global market-cap in 2015, but U.S. stocks have been the clear winners since then. Over the trailing five- and three-year periods, its average category ranks have fallen closer to the middle of the pack. If international stocks start to meaningfully outperform, this series is well-suited to benefit. The last year has been particularly challenging for the series. Rising interest rates have weighed on the passive bond index funds, which have tended to sport longer duration profiles than more actively managed peers; the longer duration has helped for most of the last decade but since rates have meaningfully moved higher since the start of 2021, it’s been a tailwind. The international bond index fund lost 2.28% in 2021, trailing two thirds of peers, and the U.S bond index fund lost 1.8%, landing squarely in the middle of the pack. The mediocre returns on the bond side contributed to the series trailing 60% of peers, on average, for the one year ending Jan. 31, 2021.”