Minnesota District Court in the Eighth Circuit Fails to Enforce the Meaningful Benchmark Requirement in the U.S. Bancorp $29 Excess Recordkeeping Fee Case

KEY POINTS: (1) The district court allows a comparator of the five lowest fee plans that plaintiffs can find. That is not meaningful of anything other than that five jumbo plans potentially had lower fees.

(2) A meaningful benchmark in an excess recordkeeping fee case would be a reliable, national benchmark of what all similarly-sized plans pay for services – not fees from a few random plans. And any such benchmark would show that $29 is a reasonable recordkeeping for a jumbo defined contribution plan.

(3) The U.S. Bancorp case is yet another excess imprudence fee case against a plan with a low-cost investment and administrative fee structure. It is an excess fee case against a plan without excess fees.

By Daniel Aronowitz, Encore [formerly Euclid] Fiduciary

A federal district court in Minnesota has ruled that the Walcheske law firm’s excessive recordkeeping fee lawsuit against a U.S. Bancorp sponsored plan with a $29 recordkeeping is plausible and will be allowed to proceed, because the complaint (1) compared these fees to estimates from five other mega plans and (2) alleged that recordkeeping fees and services for large plans are fungible. Dionicio v. U.S. Bancorp, Case no. 23-CV-0026 (D. Minn. March 21, 2024). The core reasoning of the decision is that a comparison to five other plans satisfies the “meaningful benchmark” requirement, because otherwise plaintiffs would face “nearly insurmountable pleading hurdles.”

This ruling is both unfair and illogical. It is unfair because U.S. Bancorp sponsors a defined contribution plan with very low investment and recordkeeping fees. The QDIA is a 4.5 bps Vanguard index fund. Employees who participate in the plan enjoy some of the lowest fees available for any defined contribution plan in the entire country. The U.S. Bancorp plan fees are much lower than a plan participant could get on their own in a personal IRA, or even in a retirement plan sponsored by most companies across the country. Most participants pay less than 10 bps for total plan fees. It is a model fee structure. Any fiduciary malpractice lawsuit that alleges that the plan fiduciaries failed to leverage the size of the plan to negotiate lower fees has no legitimate purpose. It is a shakedown designed to harass and extract a settlement that will only benefit the plaintiff attorneys, because the plan already has rock-bottom fees. No federal court should allow this type of lawsuit.

The ruling is illogical because a federal district court has allowed something that can be measured with certainty – recordkeeping fees paid by large plans – to be distorted with exaggeration. It is very easy to benchmark the fees paid by large plans. Companies like Fiduciary Decisions and investment advisors do it every day. It happens in every request-for-proposal that the trial bar has claimed is an essential element of fiduciary process.

But a federal district judge has held that it would be an “insurmountable” obstacle for a plaintiff law firm to plead in an excess fee lawsuit what large plans actually pay, as opposed to an estimate from a handful of plans. Instead of having to produce reliable benchmarking evidence, plaintiffs are allowed to assert that the lowest fee plans they can find is somehow the benchmark for what all plans pay. We would not allow this type of faulty logic in any other area of the law. What is so unique about recordkeeping for defined contribution plans that many federal judges stop using logical analysis? Without a legitimate benchmark requirement, all plan sponsors are sitting ducks to capricious class action litigation abuse from the trial bar.

This is another low in the long battle for a fair, uniform, national pleading standard for fiduciary malpractice in America. The following summarizes the absurd logic used in the U.S. Bancorp decision to allow an excessive fee case against one of the lowest fee plans in America.

ISSUE #1: The U.S. Bancorp plan is a low fee plan with all-in fees less than 10 bps. This is yet another example of an excessive fee case against a plan without excessive fees.

The formula for most excess recordkeeping fee lawsuits is False Fees Compared to False Benchmarks. This lawsuit was no different. The initial lawsuit alleged that the plan recordkeeping fees were $42 per participant, based on a calculation from the Form 5500 fees paid to the recordkeeper divided by the number of plan participants. This calculation overstates the amount of fees paid for just recordkeeping, because the Form 5500 includes transaction fees. There is no need to estimate recordkeeping fees, because every participant receives an account statement and quarterly fee disclosure. Plaintiff law firms know this, but alleging false and inflated fee amounts is part of the song and dance of an excess fee lawsuit.

Morgan Lewis filed a motion to dismiss the original complaint, which included the rule 404a5 participant fee disclosure showing that plan participants only pay $29 per year for recordkeeping – not the $42 that Walcheske alleged in the initial complaint. The Walcheske law firm then filed an amended complaint, asserting that the correct $29 recordkeeping fee was still excessive and based on an alleged flawed fiduciary process.

Here is what the April 2022 fee disclosure proves about U.S. Bancorp plan investments and fees:

- Alight is the recordkeeper and charges a $2.40 monthly fee. At 12 times $2.40, that is $28.80 per participant.

- We see no revenue sharing investments in the plan, so the fee is capped at $28.80.

- The plan offers five low-cost Vanguard index funds, including the Vanguard Target Retirement Date index funds as the QDIA.

- The fee for the Vanguard TDFs is .045% – only 4.5 bps.

- The performance of the Vanguard TDFs appears to be within 5% of the Vanguard Target Retirement custom index for nearly every vintage on a one-, five-, and ten-year basis.

- The plan offers four other Vanguard index funds at low fees: S. Large-Cap Index Fund (.012%); U.S. Small-Mid Equity Index Fund (.04%); International Equity Index Fund (.04%); and a Bond Index Fund (.04%). All of these funds appear to be in the lowest available institutional share class.

- The plan offers a Galliard Stable Value Fund (.29%).

- The plan offers U.S. Bancorp stock and a Piper Sandler Company Stock Fund with zero fees (.00%).

- For participants that want active management, the plan offers a managed account offered by Alight Financial Advisors (which is related to the plan recordkeeper), with a fee of .60% for the first $100,000; .45% for the next $150,000; and .30% for assets over $250,000.

We do not have the rule 408b2 plan fee disclosure, so we do not know the all-in fee of the plan. But we calculate that this plan has an all-in fee of .08-12% (and maybe even lower), making it in the top-5% of all jumbo plans over $1b in terms of low fees.

To put this into context, consider a participant with $100,000 in plan assets. That participant would have a 2.8 bps recordkeeping fee, and could choose the 4.5 bps target date funds, for all-in plan fee of just 7.3 bps. Anyone with any plan experience knows that this is historically low. Compared to all large plans over $500m in assets, this plan is among the top-1% of all plans in terms of low fees. Again, 7.3 bps is pennies – the plan is virtually free.

The premise of an excess fee lawsuit is that the fiduciaries of a large plan failed to leverage the plan’s size. The ultra-low fees of the U.S. Bancorp plan demonstrate that the fiduciaries of this plan leveraged its size to maximum advantage. There is absolutely no legitimate argument that the plan fiduciaries of U.S. Bancorp acted imprudently in managing expenses. The 4.5 bps QDIA is exhibit A to rebut any claim of excess fees, as it is a lower investment fee than just about every single defined contribution plan target-date investment option available in America today. Stated differently, this is one of the lowest fee defined contribution plans in history. 99.9% of all workers in America do not have access to a plan with recordkeeping fees under $30 and target date funds under 5 bps.

We made all of these points when the lawsuit was first filed. But the fact that a federal district judge has allowed an excessive fee case against a plan without excessive fees is disappointing. We fully understand that the world does not care if large plan sponsors are unfairly sued. But it is still a miscarriage of justice. Someone in a position of authority at the Department of Labor needs to care when fiduciary law is misapplied. At a minimum, we hope that this analysis demonstrates that excessive fee lawsuits are not about fiduciary law – they are a business model of the trial bar and growing part of the rampant legal system abuse in America.

ISSUE #2: Comparisons to the lowest fees that plaintiffs can find is not a meaningful benchmark.

As we noted above, something strange happens to some federal district judges when they are presented with claims regarding recordkeeping fees, especially lawsuits that have a chart. Many of these jurists stop applying basic logic.

The Eighth Circuit in Matousek v. MidAmerican Energy Co., 51 F.4th 274, 278 (8th Cir. 2022), held that plaintiffs asserting imprudent investment and excess fee claims must plead a “sound basis for comparison – a meaningful benchmark” to sustain their claims. You need to compare your fees or performance to something reliable and meaningful that places the fees into a proper context.

The U.S. Bancorp court held that plaintiff was using the rule 404a5 fee disclosure, and this distinguished the fees alleged from the MidAmerican decision. That is correct. The plaintiff law firm in MidAmerican used exaggerated and unreliable fee calculations from the Form 5500, alleging a false recordkeeping fee of over $500 when the actual fee was $32. It was exactly what the Walcheske law firm did in this case, when the original complaint alleged a $42 fee compared to the actual $29 fee. But now that the correct fee is at issue, the MidAmerican benchmark logic should still apply, because the correct $29 fee is being compared to the fees of just five other plans (including three years of the Fidelity plan). The same exact flaw from the MidAmerican case is found in the seven comparator plans on plaintiff’s comparator chart in the U.S. Bancorp case, because the correct fee is being compared to a fee calculated from the Form 5500. The MidAmerican case demonstrated that any fee alleged or benchmark comparison is not reliable if it is based on the Form 5500.

It is not a reliable benchmark to compare one plan’s fees to the fees of five to seven other plans. The reason is that the five to seven lowest fee plans that a plaintiff law firm can find is not a fair benchmark. Basic logic dictates that it only proves that five to seven other plans have lower fees. Nothing else. It just means that the U.S. Bancorp plan is potentially not the lowest fee plan in the country. But there is no context as what the actual universe of large plan pays for recordkeeping fees. Only a reliable, national benchmark would establish the proper context of whether the U.S. Bancorp plan fees are excessive.

The five to seven plans cited in the chart in the complaint are further biased and contrived for additional reasons. Let’s start with the chart from the complaint:

Comparable Plans’ Bundled RKA Fees Based on Publicly Available Information from Participant Fee Disclosures or Financial Statements

Plan | Participants | Assets | Bundled | Bundled RKA Fee | Record- keeper |

Leidos, Inc. Retirement Plan | 46,995 | $10,028,148,473 | $939,900 | $20 | Vanguard |

General Dynamics Corporation 401(K) Plan 6.0 |

48,852 |

$9,863,978,096 |

$1,221,300 |

$25 |

Fidelity |

Fidelity Retirement Savings Plan | 51,049 | $13,250,740,623 | $1,072,029 | $21 | Fidelity |

Fidelity Retirement Savings Plan | 57,658 | $14,730,835,962 | $980,186 | $17 | Fidelity |

Fidelity Retirement Savings Plan | 64,113 | $24,332,734,660 | $897,582 | $14 | Fidelity |

Deloitte 401K Plan | 98,051 | $9,949,148,795 | $2,157,122 | $22 | Vanguard |

Lowes 401(K) Plan | 154,402 | $5,619,838,861 | $2,856,437 | $19 | Wells Fargo |

The comparators in the complaint are four company plans for unknown years; and then three years of the Fidelity plan for its own employees (and again, the years are not identified). This means that plaintiffs are claiming fiduciary malpractice by comparing the U.S. Bancorp plan to just four plans out of all $1B+ plans in America. This is hardly a meaningful benchmark, even if it is four out of approximately 250 mega plans.

But more context is required for how and why Walcheske chose these particular plans. Despite holding out these comparator plans as paying “reasonable” and “prudent” recordkeeping fees, four out of five of the comparator plans have been sued for failing to prudently monitor their fees and investment options. The General Dynamics plan was one of the first plans to be sued in 2006; Deloitte was sued in 2021 for allegedly paying $65 per participant in recordkeeping fees; and Lowes was sued in 2020. What plaintiffs fail to mention is that they are comparing U.S. Bancorp to plans that have reduced their fees under pressure of a lawsuit. These are artificial comparators.

The comparison to three years of the Fidelity employee plan is also misleading. The Fidelity plan was sued for excess fees in Moitoso v. FMR LLC., No. 1:18-cv-12122 (D. Mass. 2018). In the lawsuit, Fidelity stipulated to certain facts “for purposes of [that] litigation only” to satisfy its discovery obligations to plaintiffs. But the stipulation does not state that the Fidelity plan actually paid an annual $14 to $21 per-participant recordkeeping fee; it states only that these amounts reflected “the value of the recordkeeping services that Fidelity provided to its own plan at the time.” Fidelity has since made clear that the stipulation was entered into “for the limited purpose of resolving a discovery dispute” and “certainly does not reflect the value of the recordkeeping services that Fidelity provides to different plans pursuant to different recordkeeping contracts for different sets of services.” A number of courts rejected fee comparisons based on this same Fidelity stipulation. See Wehner v. Genentech, Inc., No. 20-cv-06894-WHO, 2021 WL 507599, at 6 (N.D. Cal. Feb. 9, 2021) (refusing to draw any inference from the Moitoso discovery stipulation); Johnson v. PNC Fin. Servs. Grp., Inc., No. 2:22-CV-01493-CCW, 2021 WL 3417843, at *4 (W.D. Pa. Aug. 3, 2021) (same). But that has not stopped the Walcheske and Capozzi law firms from using the Fidelity discovery stipulation as a purported benchmark in dozens of the cases. It goes without saying that Fidelity is the leading recordkeeper in America. Why they charge their own employees anything is one thing, but whatever they charge their own employees cannot possibly be a valid benchmark for judging the fiduciary prudence of the fiduciaries of other jumbo plans in America.

ISSUE #3: It is not an “insurmountable” pleading standard to place plan fees in a proper context with a national, reliable benchmark.

The Minnesota District Court justified its ruling by asserting that it would be an insurmountable burden for plan participants to sue plan fiduciaries if they were required to supply a better benchmark. Again, something strange happens to the logical analysis of federal district judges when are presented with defined contribution recordkeeping.

It is not an insurmountable burden to require plaintiff law firms to present a reliable, national benchmark when they want to sue a large plan for excessive fees. It is the least that they can do when they sue for fiduciary malpractice.

The real reason that plaintiff law firms do not provide a reliable, national benchmark is not the burden. Rather, the reason plaintiff law firms do not provide a full-market benchmark study is that it would immediately debunk most of their cases alleging excessive fees. It would ruin their business model. They could easily commission a study of what large plans actually pay for recordkeeping fees. It is not an insurmountable task. But it would end the excess fee lawsuit charade. Plaintiff law firms do not commission a recordkeeping fee study, because it would show that most of the plans they sue have reasonable recordkeeping fees.

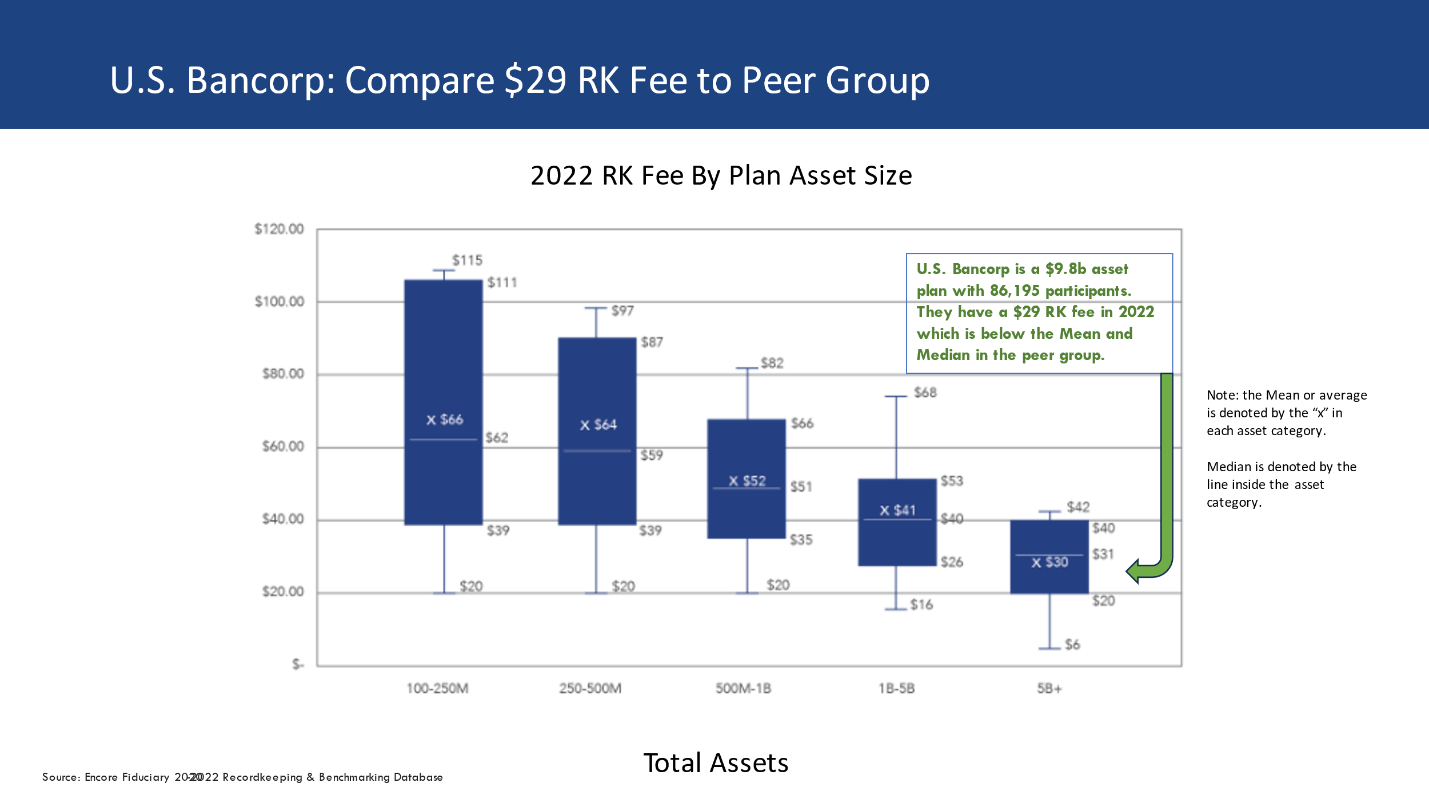

Encore Fiduciary has published a reliable, national benchmark of what large plans pay for recordkeeping fees. It is based on fee disclosures of large-plan sponsors. Here is what it shows for the $29 recordkeeping fee of the U.S. Bancorp plan that the Walcheske law firm claims is excessive and must be based on a faulty and imprudent process:

The Encore recordkeeping benchmark for plans with $5B and higher assets reveals that 80% of all plans of this size have recordkeeping fees between $20 and $40. The average recordkeeping fee for these jumbo plan sis $30, and the median is $31.

This means that the U.S. Bancorp $29 fee is below both the average and median for jumbo plans with assets over $5 billion. There are a few plans with lower recordkeeping fees, but the U.S. Bancorp recordkeeping fee is reasonable. Period – end of story.

Except it isn’t the end of the story. U.S. Bancorp and its fiduciary insurers will have to spend millions of dollars on legal and expert fees to prove this its fees are reasonable – all because a trial firm convinced a federal judge that its excessive fee claims were plausible. But the complaint was based on a chart of five plans with purportedly lower fees – not the truth that more than 50% of all jumbo plans have recordkeeping fees above U.S. Bancorp’s $29 fee.

Finally, the U.S. Bancorp court reviewed all of the cases that have considered the trial bar contention that large-plan recordkeeping is a fungible commodity that is undifferentiated by levels of service. The court said that there is “no clear consensus has emerged,” but “the majority of judges addressing specific allegations regarding the fungibility and commodification of recordkeeping services have found the excessive-fees claims to be plausible.”

We do not understand why federal judges are deciding whether large-plan recordkeeping is a commodity at the motion to dismiss stage without any evidence. But the issue is a red herring. SPARK and the recordkeeping industry needs to provide thought leadership addressing this issue, demonstrating that there are service-level distinctions in recordkeeping services. Nevertheless, the Encore national benchmark demonstrates that we should not even get to the level of services issue in most cases. If judges require plaintiff lawyers to produce a national benchmark of what all plans pay, most cases would be dismissed when it is shown that the fees charged are within a reasonable range of what other funds pay – even if the service and quality level is different.

The Encore Perspective

The U.S. Bancorp ruling is unfair and illogical. The ruling is an open invitation to plaintiff law firms to sue any plan. The pleading standard only requires plaintiffs to find a handful of plans with lower fees. And they don’t even have to prove that those fees are accurate.

The ruling is especially disappointing from a district court in an appellate circuit that requires a meaningful benchmark. Plaintiff law firm are asserting in the First Circuit [see most recently the Cape Cod Healthcare excess fee lawsuit] and the Fifth Circuit [see the American Airlines covert ESG lawsuit] that they have unfettered discretion to file excess fee and investment performance lawsuits, because those Circuits purportedly do not require a benchmark. But it is more disappointing when a district court in the Eighth or Tenth Circuits water down the meaningful benchmark requirements. It has allowed an excessive fee lawsuit to proceed against a plan with some of the lowest fees of any plan in the country.