KEY POINT: The excess fee case alleged a $19-22 recordkeeping benchmark invented by a serial plaintiff-side recordkeeping “expert” with no proof that any plan in the country actually paid the made-up low fee.

The Fid Guru Blog has exposed many excessive fee cases that allege false fees, and then compare them to false benchmarks, all designed to fool federal judges into allowing cases to proceed past a motion to dismiss as “plausible” fiduciary breach claims. The PNC excessive fee case fits this template. The complaint alleged a “shocking breach of fiduciary duty” (1) with false fees [$55-$85 per participant when the actual amount was $46 and declining each year to well under $30], (2) compared to just four plans out of the entire universe of defined contribution plans. The comparison was not a credible national survey that would give context and perspective as to how the PNC recordkeeping fee would compare to all other plans, but just four plans with unverified fees, cherry-picked to create the impression that PNC’s fees were astronomically high because the purported reasonable fee would be $14-21. You wouldn’t even know from the complaint how PNC’s plan compared to the national average or median plan fees.

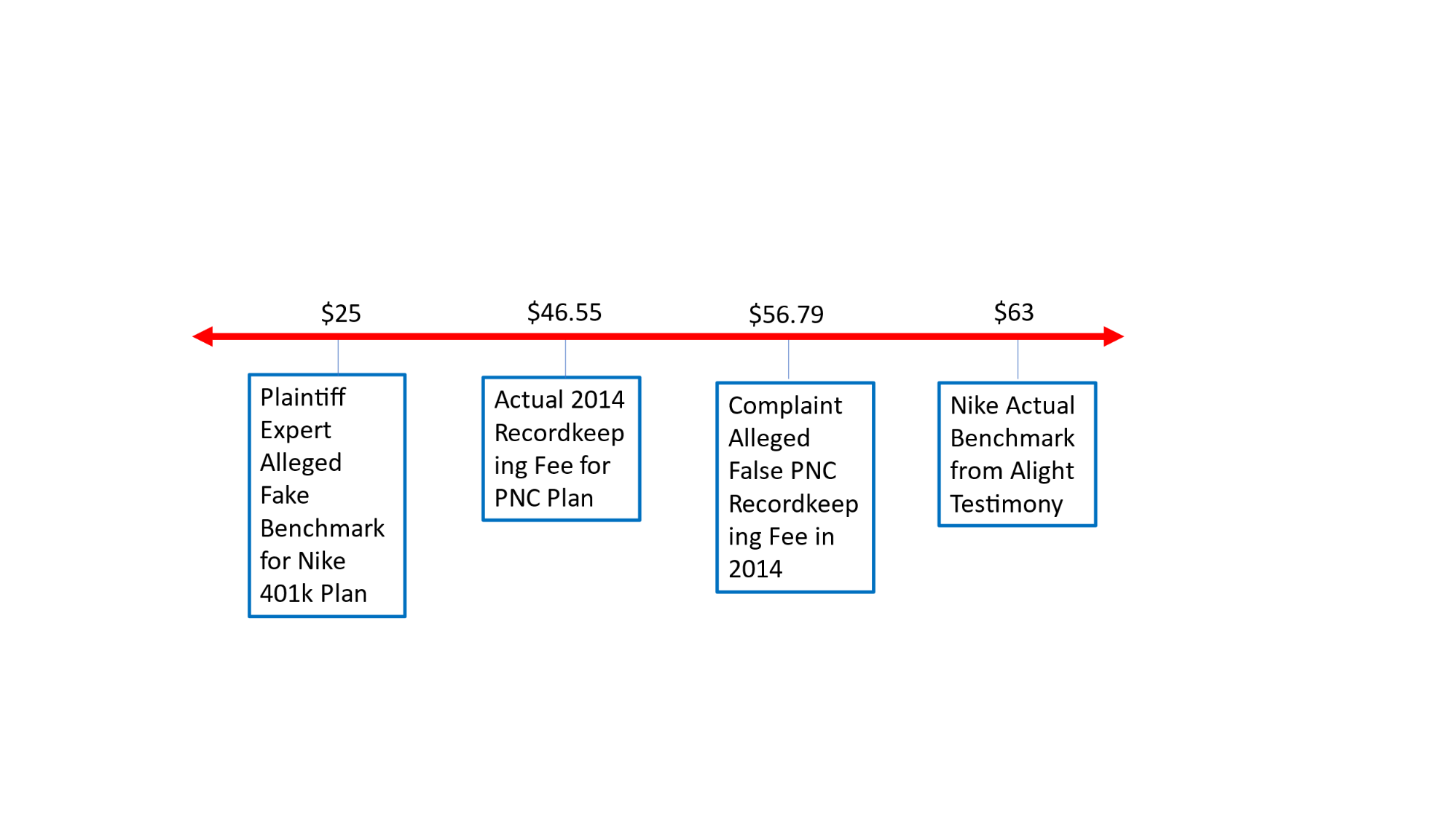

The PNC case, however, exposed a third key element of the plaintiff’s bar excessive fee con game, and that is false expert testimony with fee benchmarks plucked out of thin air. Whereas most cases settle after a court holds that the comparison to four random plans shows a plausible claim of fiduciary imprudence, PNC forced plaintiffs to prove their case with actual evidence of excessive fees. Plaintiffs filed an expert report from a former Transamerica employee who alleged an arbitrary low recordkeeping amount of $19 to $22 based on no credible methodology. He made up his own personal benchmark, inventing the “reasonable” amount based on his gut feel from his fifteen years of “experience” – and then found plans to support his contrived fee target. Even his fee evidence was false. For example, he misrepresented his comparator of the Nike 401k Plan by a factor of three: $20 compared to the actual fee of $63, which was higher than PNC participants paid for recordkeeping fees. Talk about “shocking.”

Plaintiff’s expert had no evidence that any plan in the entire plan universe actually paid the contrived benchmark upon which he based his testimony. This same “expert” spouting junk recordkeeping evidence has testified in many cases, all designed to extort a settlement that benefits the plaintiff firm and the expert witness. This false evidence is similar to what the plaintiff bar has used in hundreds of cases to profit off a false narrative that America’s large-plan sponsors pay excessive administrative fees. It is a big lie.

Here is the question: Should federal courts allow the plaintiff bar to file fiduciary malpractice cases premised solely on comparisons to a few random plans? The answer is no. We must have a higher standard to plead fiduciary imprudence for alleged excessive fees because too many plan sponsors with reasonable fees are having to defend meritless cases. Surely the “plausibility” pleading standard requires real proof, not misleading comparisons designed to extort settlements.

The Pennsylvania federal court in the PNC case served as a gatekeeper to exclude junk expert evidence to grant summary judgment. But this same unreliable evidence is what the trial bar uses to file these complaints in the first place. These cases should be dismissed at the preliminary stage of the case unless supported by actual and reliable national benchmarks – not the type of fake evidence revealed to be fraudulent in the PNC case. As fiduciary law gatekeepers, federal courts must demand reliable evidence upfront – not at the summary judgment or trial stage when faced with junk expert evidence. Plan sponsors should not have to defend against fake cases that are brought under false and fraudulent pretenses.

The easy solution is to require the plaintiff trial bar to (1) allege correct fees based on actual plan contracts or fee disclosures; and (2) then compare actual fees against a national benchmark survey to assert fiduciary imprudence – not misleading citations to a handle of random plans. Why won’t the ERISA plaintiff bar base their complaints on a credible national benchmark study of recordkeeping fees? What are they are afraid of? The answer is easy. The gig would be up if they had to file cases based on real proof.

The PNC case is worth studying because it follows the same misleading template of most other excess fee cases: false fees compared to false benchmarks, and then supported by unreliable and false expert testimony. After demonstrating the use of fake fees, benchmarks, and junk expert testimony, we end with an analysis of a few key points.

The PNC Excess Fee Case: A Complaint Alleging a “Shocking Breach of Fiduciary Duty” With No Actual Proof

When evaluating any ERISA excessive fee case, you have to start with what the plaintiff law firm claims that they will prove at trial. Then you need to compare it with the actual evidence that is adduced during discovery or at trial. That is how you can prove that many excessive fee cases represent manufactured and fake claims based on flimsy and made-up evidence. The PNC case proves all of these points.

The Miller & Shah law firm – infamous for filing twelve lawsuits alleging that plan fiduciaries committed malpractice for chasing the low fees of the #1-rated BlackRock LifePath target-date funds based on manufactured claims of investment underperformance – filed a breach of fiduciary duty lawsuit against PNC Financial Services Group and the fiduciary committee for the PNC Financial Services Group, Inc. Incentive Savings Plan Administrative Committee on October 2, 2020. The Complaint alleged that the PNC fiduciaries of the $5.7B plan with 66,032 participants “engaged in a shocking breach of fiduciary duty” by allowing plan participants to pay between $85.18 in 2014 to $89.70 in 2018 for plan administrative services. The recordkeeping fees were estimated to range between $56.79 in 2014 and $50.99 in 2018. With no support, the complaint alleged that the proper recordkeeping fees would be $14 to $21 per participant. The only purported benchmark for recordkeeping fees was a citation to the 401k Averages Book (20th Edition) that “the average cost for recordkeeping and administration in 2017 for plans much smaller than the Plan (plans with 100 participants and $5 million in assets) was $25 per participant.” This is totally false. Page 58 of the 401k Averages Book for the year cited shows revenue sharing of $320 + $40 in direct recordkeeping = $360 per participant. The misrepresentation of the 401k Averages Book is – using Miller Shah’s own word – shocking!

On August 3, 2021, the Western District of Pennsylvania court granted PNC’s motion to dismiss this flimsy complaint. The court stated that “Plaintiffs’ allegations stop short of crossing the threshold from possible to probable.” [ENCORE NOTE: The pleading standard from the Supreme Court in Hughes v. Northwestern is “plausible,” not probable.]. The court accepted PNC’s argument that the complaint failed to account for revenue sharing, and thus “smaller plans pay much more according to The 401k Averages Book.” As for the $14-21 purported benchmark, the court stated that plaintiffs claimed that this came from the Moitoso case challenging recordkeeping in Fidelity’s own plan, but held that plaintiffs needed “additional detail about the Plan’s fee structure and the services received in exchange for those fees.” This was influenced by the fact that recordkeeping fees had fallen during the six-year time frame of the complaint. The court thus held that “Plaintiff’s allegations raise the possibility that Defendants acted imprudently, but stop short of state a plausible claim for breach of fiduciary duty.” [ENCORE NOTE: this time the court got the “plausibility” standard correct].

Two weeks later, on August 17, 2021, Miller Shah filed an amended complaint. The plan had grown to $6.9 billion in assets, with 65,410 participants. The complaint alleged that the recordkeeping fees were $56.79 in 2014 and $46.43 in 2019, with an average of $3,357,723 per year, or $52.58. The amended complaint omitted the misrepresented citation to the 401k Averages Book. The purported benchmark in the amended complaint compared the PNC Plan of 66,032/$5.676B and an average recordkeeping with Alight of $50.99 [yes, the numbers keep changing, but this is not an exercise in truth] to just four other plans that allegedly have Alight as the recordkeeper: (1) The Rite Aid 401(k) Plan [$31,330/$2.668B = $33.20 RK fee]; (2) Advocate Health Care Network Retirement Savings 401(k) Plan [44,893/$2.955B = $31.66 RK fee]; (3) Proctor & Gamble Profit Sharing Trust & Employee Stock Ownership Plan [53,048/$17.465B = $31.69 RK fee]; and (4) UPMC 403(b) Retirement Savings Plan [53,206/$2.140B = $25.30 RK fee].

The table of four comparator plans did the trick, as the same federal court denied PNC’s motion to dismiss the amended complaint. PNC argued that plaintiff relied on a “non-representative, cherry-picked 401(k) benchmark comparison,” which does not permit any valid inference that PNC’s fiduciary process was imprudent. The court nevertheless found the comparison of $52.58 to “four other 401(k) plans noted within Plaintiff’s benchmark table comparison was sufficient to raise an inference that Defendants failed to scrutinize the prevailing rates for the recordkeeping services received by the plan and failed to follow a prudent process to ensure that the plan was paying only reasonable fees.” The court noted that ERISA plaintiffs generally lack the inside information necessary to make out their claims in detail unless and until discovery commences. The court concluded that “[w]hile it may turn out that the terms of the recordkeeping arrangements were prudent under the circumstances, that is not the relevant inquiry at this juncture.”

In other words, the court gave the benefit of the doubt to plaintiffs. There is no evaluation of whether the fee claims were true – just a presumption in favor of the plaintiffs. The question we continually pose is whether this is fair to plan sponsors. These lawsuits are based on false evidence of fees, which negates the justification for a presumption in favor of plaintiffs. The PNC case proves our point.

The Testimony of Plaintiff’s Expert Ty Minnich

After the case was allowed to proceed to discovery, plaintiffs had to prove that the plan’s fees were actually excessive. They did this with an expert report from Ty Minnich. Mr. Minnich is infamous for serving as an expert in many excessive fee cases. He is the same expert used in the Boston College, Cornell, USC and Yale cases. The Cornell court excluded Minnich’s expert report because it was based on unreliable methodology. In the Cornell case, he stated “in conclusory fashion what the reasonable fee were, but did not explain how his experience led to this conclusion.” The Cornell court found that Minnich offered no explanation as to how he chose his comparator plans. They just “happen to be indicative of the analytic components [he] was looking at to come up with the reasonable fee.” In the Boston College case, the court excluded portions of Minnich’s expert testimony because there was “no indication as to how he applie[d] any methodology to calculate a reasonable fee.”

The PNC court excluded Minnich’s testimony for the same reasons that he used an unreliable methodology that was based on no real-world plan data. He could not identify a single plan that paid the low $19-22 amount that he proclaimed would have been reasonable for the PNC plan. Just like in the Cornell and Boston College cases, he invented his market rate, then cherry-picked comparator plans to support his invented fee amount.

Specifically, Minnich’s expert report contended that the reasonable market rate for the PNC recordkeeping and administrative services was $22 for 2014-2016, $20.00 for 2017-2019, and $19.00 for 2020-2022. Based on this estimated reasonable market rate, Minnich calculated that the PNC plan had a total of $25,122,442 for paying excessive recordkeeping fees. PNC moved to exclude Minnich’s expert testimony, arguing that it is not reliable because his opinion is based solely on his experience without using any reproducible or traceable process.

Minnich asserted that he based his expert opinion on his industry experience and three pertinent factors: (1) participant count; (2) the services provided; and (3) any ancillary revenue to the recordkeeper for additional plan services [i.e., if you chose the recordkeeper’s investments, you get a lower fee]. Minnich explained that participant count is the most important to determining how a recordkeeper prices an account, explaining that “[w]hen the number of participants increase, the necessary recordkeeping fees would exponentially decline.” He further explained that recordkeepers often create a pricing curve based on participant count and per person fees to determine the reasonable market rate.

Even though Minnich claimed that a pricing curve is the key to evaluating a reasonable market recordkeeping fee, he did not create a pricing curve in the PNC case despite indicating this is the industry norm. By contrast, in the USC and Yale cases, Minnich compiled a list of similarly-sized comparator plans, identified their per person fees, plotted the fee and size information on a pricing curve, then used this curve to determining the reasonable fee. Minnich could not point to any other reliable methodology or scientific procedure he used to calculate his reasonable fees for the PNC plan. Instead, the court held that his opinion appears to be based on “his subjective belief and experience.” He thus could not demonstrate that his testimony was more likely than not the product of reliable principles and methods. The defense characterized it is as a “take my word for it” standard – his own personal benchmark.

Minnich also pointed to four other retirement plans that he believes were comparable to the PNC plan that demonstrated that PNC “could have negotiated far lower recordkeeping fees.” But the court held that these four plans “do not salvage the reliability” of Minnich’s opinion, because “[i]t appears that after Mr. Minnich determined the reasonable market fee, he then picked these plans to support his reasonable fee determination.” This is the same type of expert opinion that he offered in the Cornell case when he offered no explanation as to how he chose his comparator plans. He selected his comparators with fees that supported his calculations, which the court held were not based on a reliable methodology or process he used to calculate the reasonable market fee. The key point is that he could not identify a single other plan in the market that ever paid his “reasonable market rates.”

The flaws in his expert testimony go beyond the fact that he invented his market rates, and then found plans afterwards to support his flawed his analysis. Even the plans he used were based on unreliable data from publicly filed Forms 5500. Minnich conceded that Form 5500 data filed online to the public “may not be a reliable source of information to identify the full amount of recordkeeping fees that a particular plan paid in a given year.” Defense lawyers from Morgan Lewis applied Minnich’s process to Forms 5500 for other mega plans, revealing the skewed and self-serving nature of Minnich’s pricing comparators. Applied to other mega plans with Alight as a recordkeeper in 2018, for instance, the process reflects much higher recordkeeping fees: $57.01 for the 3M Plan; $77.16 for the BAE Plan; and $52.87 for the DXC Plan. Extending the exercise to Transamerica plans where Minnich worked prior to becoming an expert witness for the plaintiff bar, reflects similarly high fees: $67.83 for the Aurora Health Plan; $66.80 for the NY Presbyterian Hospital Plan; and $78.25 for the Northwell Health Plan. Allowing complaints based on Form 5500 data is allowing fake evidence, because the data is not reliable.

The plans used to justify his “Trust Me” Benchmark were also false. For example, Ty Minnich alleged that Alight was the recordkeeper for the Advocate Health Plan at an amount of $31.66. But Alight submitted an affidavit testifying that it was not the recordkeeper for the Advocate Plan. The Rite Aid plan was used by Minnich, but he included only direct recordkeeping fees, and not indirect recordkeeping fees. The fees he alleged from these plans are not accurate.

The most damning element of Minnich’s expert report was his misrepresentation of the Nike 401k Plan. Minnich testified in his expert report that Alight was the recordkeeper for the Nike 401k plan and charged participants $20 to $28. This was false. Alight filed an affidavit that it served as the recordkeeper for the Nike Plan for the years 2012 through 2018, and its “base fees for Alight’s recordkeeping services for the Nike Plan were $63.00 per participant annually.” He misrepresented the Nike plan fees by a factor of three. The Nike plan was higher than the fees of the PNC plan was supposedly based on a “shocking breach of fiduciary duty.” As discussed below, the Minnich report was junk.

The following chart is useful to demonstrate how plaintiffs used false evidence to convince the federal court to allow the case to proceed. It is a useful guide as we make some additional points from the junk expert evidence in the PNC case.

KEY POINT #1: The alleged “shocking” high fees alleged in the original and amended complaints were false – the only thing “shocking” was the outrageous misrepresentation to the federal court. Nevertheless, the false fees were presumed true, even though the fees could be objectively verified with little effort by the federal court at the pleading stage.

As noted in the introduction, the PNC case followed the excess fee case formula of (1) fake fees (2) compared to fake benchmarks. It started with fake fees. The original complaint alleged that 2014 recordkeeping fees were $56.79 [and $85.18 overall with an additional administrative fee]. The amended complaint alleged that the recordkeeping fee was also $56.79. The June 21, 2024 summary judgment opinion cited the true recordkeeping fees: “[i]n 2014, the Plan’s base recordkeeping fee was $46.55 per participant, and it declined to $32.00 per participant by January 1, 2022.” Just to be clear, the complaint alleged $56.79 when the actual fee was $46.55 in 2014. PNC’s fees declined from $46.55 to $32 – a track record of good fiduciary process.

The PNC complaint is another in a long-line of excessive fee claims in which the fees alleged were false. This is important if the pleading standard is going to assume that everything a complaint says is true. Nothing in an excessive fee complaint should be presumed true, especially when the false allegations can be verified with plan documents. The track record of intentional misstatements by the ERISA trial bar does not warrant the presumption of anything, other than a presumption of mistrust. The presumption should be that the complaints are false without real proof, because they almost always false.

The plaintiff’s bar argues that they have insufficient information at the pleading stage and that is why they should get the benefit of the doubt. This is a makeweight argument. It may be true about the plan sponsor’s fiduciary process, but not the actual fees paid by the participants who are recruited by the plaintiff bar to serve as plaintiffs. We note that the participants in the PNC case had such tiny accounts that they didn’t even pay $25 in RK fees. But the key point is that the exact fees paid by participants are not a mystery. Federal judges might not understand how it works, but it is not complicated. Plan participants can log onto the Alight recordkeeping platform and know their account balances and fees paid on a 24/7 basis. Alight also sends quarterly fee disclosures. The plaintiff bar should not be allowed to “estimate” fees in order to intentionally overstate and misstate the plans fees. The actual fees are available to every participant. The type of false fees alleged in the PNC case is a scam. The fact that Miller Shah alleged incorrect fees in an excessive fee cases should be an outrage.

The easy lesson to federal courts: allow plan sponsors to correct the record with actual plan fees in any case alleging fiduciary breaches for excessive fees.

KEY POINT #2: The Fees Alleged in Plaintiffs’ Expert Report Were Based on False “Junk Science” – for example, the Nike Plan Fees Were $63 Compared to the $20 Fake Testimony of Ty Minnich [higher than the actual PNC fee].

The PNC case was based on expert testimony that amounts to “junk science.” It is a term of art that refers to researcher biases, poor scientific procedures, and errors in reasoning. Debunked theories are consider “junk science.” As the Expert Institute states, “[l]ike junk food, junk science is devoid of substantive, useful content – no matter how appealing it might seem in the moment.” The federal courts have constructed expert witness standards to eliminate junk science from modern trials. Under Federal Rule of Evidence 702 and the Supreme Court’s decision in Daubert v. Merrell-Dow Pharmaceuticals, federal judges have a gatekeeping role to ensure that expert witness testimony is: (1) based upon sufficient facts or data; (2) the product of reliable principles and methods; and (3) the witness has applies the principle and methods reliably to the facts of the case.”

In case after case, the plaintiff bar is using expert evidence that cannot be justified by a single plan that actually pays what the experts allege. This is junk science. The Minnich expert report in the PNC case, like his testimony in the Cornell and Boston College cases, was based on his “say-so.” His calculation of $25m+ in losses amounted to no more than conjecture or speculation. He derived the damages model from his experience working for Transamerica. But experience is not a methodology. “Take my word for it” is not a reliable methodology.

The junkiest aspect of Minnich’s testimony was his attempt to validate his invented benchmark with a comparison to four random plans. The fee evidence from the four plans was inaccurate. His chart of the fees of the Nike Plan derived from Form 5500 data was a work of fiction. He claimed that the Nike 401k plan had $20-$28 recordkeeping fees with Alight. But Alight filed an affidavit stating that the fees were actually $63. It was an outrageous misrepresentation. It certainly exposes the con game of the excessive fee trial bar.

Like the federal court in the PNC case, federal courts are acting as gatekeepers of junk science in excess fee cases. We have seen plaintiff exert testimony excluded in many cases now, including the excess fee cases against, TriNet HR, MedStar Health, Thermwood Corp, Banner Health, Oracle, Cornell and Boston College. It is becoming the most valuable defense weapon in disproving excessive fee fiduciary breach cases.

It is helpful that courts are excluding junk expert evidence in excess fee cases. But most of these cases should never get to the expert witness stage. The fact that so many cases are based on junk science should inform federal judges that the ERISA trial bar is not worthy of any presumption in their favor at the pleadings stage. Cases based on junk evidence of excessive fees should be dismissed unless plaintiffs can validate their claims with (1) reliable evidence of the actual fees charged, (2) compared to a reliable, national benchmark that gives context and perspective as to whether the challenged plan actually has egregiously high fees. The purveyors of junk science do not deserve any presumption that their complaints are plausible.

KEY POINT #3: Comparisons to four to six random plans out of thousands of jumbo plans is not reliable evidence of what plans actually pay. Federal courts as gatekeepers of fiduciary law must demand reliable, national benchmarks at the pleading stage.

If I told you that I knew the winner of the presidential election because I surveyed four voters, you would tell me that I didn’t have reliable evidence of the potential outcome. I would need a credible sample of the voter pool. If I told you that I surveyed six random people, and they told me that the most popular streaming service is Peacock, you would tell me that I need a better sample size. What if I told you that your 5,000 square-foot home is overpriced at $1.2m, because I found four examples of homes with the same square footage priced at $1.0m. You would tell me that my random sampling is not a reliable indicator of what your home is worth. I would need to back up my speculative claim with real data: a real survey in the same neighborhood that considered other factors, including quality of the house and other features that affect the price, like whether one house had a pool, better appliances, or a better location or school district. You wouldn’t sue your real estate professional for professional malpractice for causing you to overpay by $200,000. You would demand better evidence.

So why is it that federal judges across the country are allowing unverified evidence of four to six random plans out of all of the plans in America to serve as “plausible” evidence in an excessive fee case? What is so special about retirement plans that causes federal judges to stop using logic? There is no good reason. Judges must demand better evidence. The pleading standard for fiduciary breach cases is not “possible” – it is plausible. There is a range of evidence from possible to plausible to probable. Evidence of four plans with lower fees might be possible evidence that a higher fee is a result of imprudence. But is not plausible, especially after so many cases have been demonstrated to be supported with fake evidence from unreliable “experts” who testify serially in these cases. Plausibility demands more evidence.

Is it too much to ask for the application of a reliable, national benchmark? What is the trial bar afraid of? They are afraid of the truth. And the truth is that most of their excess fee cases are bogus – based on made up, misleading claims. Most of the cases are against plans with average or below average fees. But you would not know it, but no case has required a national benchmark study to validate how the fees actually compare to the entire plan universe.

Ask your neighborhood “For the People” plaintiff lawyer advertising on billboards why they are afraid of a requirement to allege fees based on a reliable, national benchmark, and not unverified random plans. If they took a truth serum, they would tell you that a national benchmark study of plan fees would undermine nearly every case they file. The excess fee trial bar would be out of business.

KEY POINT #4: The PNC case shows a key difference in plan RK pricing: If you have investments from the recordkeeper, you get a lower fee. This point alone demonstrates why you cannot just allow a chart of random plans without digging deeper into other key differences.

The plaintiff bar asserts in every excess fee case that recordkeeping fees are commoditized and that plan services for large plans are basically the same for every plan. They get away with this assertion because courts give them the presumption of truth at the pleading stage. But they get away with it because recordkeepers and plan sponsors have done a poor job rebutting this contention. There are legitimate service quality differences, and there are differences in services provided, including participant communication and dedicated personnel for every account. The quality of the recordkeeper’s platform matters. And so does the quality of cybersecurity protections. Even Minnich testified that the second driver of higher recordkeeping fees are core and enhanced services, such as providing participant loans, QDROs, and other services. Recordkeepers have meaningful differences in services, and it is not fully commoditized. We must do a better job of documenting these differences to rebut the premise that all recordkeepers are alike.

In any event, the testimony of Ty Minnich provides a key difference in rates for recordkeepers. He testified that recordkeeping fees are based primarily on participant count. But he noted that recordkeepers will consider additional revenue streams in pricing plans, and “will often be willing to offer recordkeeping services at or below cost for plans that have the potential to produce large additional revenue streams.” He identified additional revenue sources that are not related to recordkeeping, such as the use of a recordkeeper’s proprietary investments options in the plan, IRA rollovers, cross-selling insurance products, managed account services, and the use of wealth advisors for employees with higher account balances. He noted that Alight in 2020 received $2,252,361 in participant investment advisory services from PNC plan participants.

Minnich is right about additional revenue streams to recordkeepers. Large plans that use proprietary investments from the recordkeeper have lower recordkeeping fees. Plans that use the managed account or other services from the recordkeeper can negotiate lower fees. Consequently, you cannot compare the fees of four jumbo plans and derive any meaningful insight to whether the fees are reasonable. Minnich might not realize it, but his testimony about ancillary revenue undermines his already faulty expert testimony. You cannot compare the Nike and Rite Aid plans to the PNC plans without evaluating ancillary revenue to the recordkeeper.

This key insight is missing from the defense of excess fee cases. It is the only redeeming value of the Minnich testimony in the PNC case. But you learn from everyone, even a junk scientist.

KEY POINT #5: Plaintiffs in the PNC case used a 2022 RFP with a lower fee against the plan sponsor.

We end with one final point that is easy to miss in the PNC case, because it does not appear in the summary judgment opinion. The primary argument by plaintiffs in opposition to PNC’s motion to exclude the testimony of Ty Minnich was that PNC conducted a recordkeeping RFP after the case was filed in 2022. The RFP resulted in lower fees. The amount is redacted, so we assume it is a really good rate that Alight wants to hide from the public. It is also possible it is redacted because it is unfair to use the RFP results against PNC. But that is exactly what plaintiffs tried to do.

This is the third recent case in which we have seen plaintiffs use the results of RFPs in order to argue that the sponsor’s RFP validated their excessive fee claims. We make this point so that plan sponsors are aware of the downside of RFPs. If you conduct a RFP, you need to understand that it will be used against you as proof that you were negligent in prior years. It is also important to know that you must be prepared to follow through with the RFP. If you don’t want to replace your vendor, be careful in an RFP, because it creates a record that can be used against you.

FINAL THOUGHTS

The PNC case is just another example of how the excess fee recordkeeping premise is a big lie. We have seen another big lie in recent years. Over sixty cases were filed alleging that the 2020 election was rigged. Many of these cases claimed fraudulent ballots and even rigged voting machines. The courts threw out every single case for lack of evidence. They didn’t presume the truth of any invalid claim. They demanded upfront proof before allowing the claims to proceed. The election rigging cases have been referred to as the Big Lie.

We are asking for the same pleading in excess fee cases. It is not asking for much. It is super easy to validate that plaintiffs are alleging the actual fees charged by the plan. Every participant has a quarterly fee disclosure, and online access to their account any moment of the day. Estimations of fees from unreliable public filings is just wrong. The same goes for comparisons to justify claims of excessive fees. Comparisons to four plans based on the same unreliable form 5500 data is not reliable evidence. It is very easy to require a reliable, national benchmark from which to compare actual plan fees. Fiduciary Decisions will be happy to provide a reliable benchmark to judge the plausibility of excess fee cases. Our team at Encore Fiduciary has our own benchmark that gives context and perspective.

We have our own Big Lie in the retirement plan community. It is that large plan sponsors like PNC have allowed recordkeepers to charge excessive fees. These cases are based on false fees that are compared to false benchmarks. And then in the few cases in which the plan sponsor fights back, the plaintiff bar then resorts to fake, junk evidence. It is a Big Lie. It is time to put an end to the Big Excess Fee Lie.