A core group of plaintiff law firms play the role of the ERISA police to accuse corporate sponsors of large benefit plans of fiduciary breaches in class-action lawsuits. The list of purported fiduciary breaches keeps growing, with the current flavor of the month involving alleged breaches for plan forfeitures and pension risk transfers. But the most frequent, bread-and-butter ERISA class action lawsuits allege that large plan sponsors have improperly allowed Fidelity, Empower and other recordkeepers to charge participants excessive plan administration fees. Like clockwork, the Walcheske & Luzi law firm files at least one excess recordkeeping fee case each month. Led by a former law professor, they have done this for years. Like the rampant product liability lawsuits alleging that Roundup causes cancer, these cases have nothing to do with the truth. It is a litigation scam that exploits the weak pleading standards in the federal courts.

The Walcheske excess fee playbook is the same in every case: (1) allege inflated and false recordkeeping fees based on the Form 5500 public filing that includes participant transaction fees that do not relate to recordkeeping; (2) ask the court to infer fiduciary malpractice by comparing the inflated fee amount of the targeted plan to unverified recordkeeping fees of three to five random plans sponsored by other companies with unverified data that does not include participant transaction fees; and (3) then allege that all large-plan recordkeeping services are commoditized – that the only difference in recordkeeping fees charged to plans is based on participant count or plan size. Many courts accept the commodity assertion at face value as “true” for purposes of a motion to dismiss in federal courts, and thus plaintiff law firms are able to leverage the high cost of litigation to leverage settlements.

America’s defined contribution recordkeeping firms have done nothing that we can discern to help their plan sponsor clients combat these frivolous lawsuits. Recordkeepers sit back and watch their clients get sued over and over. The fiduciary breach case is about the fees they collected, but to my knowledge no recordkeeper has attempted to combat this litigation abuse with public data demonstrating that most plans being sued have reasonable recordkeeping fees. And we have not seen anything from the recordkeeping industry refuting the claim that recordkeeping fees are commoditized, which has allowed plaintiff law firms to torment large-plan sponsors for over a decade. Instead, America’s recordkeeping firms have allowed their clients to get sued one after another as they have sat on sidelines.

Two current victims of the Walcheske excess recordkeeping playbook are U.S. Bancorp and Tysons Foods. Both plan sponsors have reasonable recordkeeping fees when compared to Encore national benchmarks, but they must nevertheless defend their recordkeeping fees in frivolous lawsuits. A court has already denied the motion to dismiss against U.S. Bancorp, forcing the company to defend its low $29 recordkeeping fee – a fee that our benchmarks reveal is well below the average paid by similarly sized plans.

Given the lack of industry support to combat ERISA litigation abuse, it is thus gratifying to see an August 2024 recordkeeping study by CEM Benchmarking entitled An Empirical Analysis of the Drivers of Record Keeping cost in U.S. Defined Contribution Plans. We thank Steven Gissiner of Orchard Hills Consulting for alerting us to this new study. The study analyzes how plan size, managed accounts, and choice of investment manager affect recordkeeping costs. The survey of over 100 jumbo plans quantifies that these jumbo plans pay between $20 and $80 per participant for recordkeeping. This significant range means that recordkeeping services are not commoditized. There is a difference in the complexity of plan sponsor payroll integration, participant service standards, and quality of service. Indeed, some plans pay for a “white glove” higher standard of service.

Beyond service quality, the key CEM finding is that the number one way to discount recordkeeping fees is by offering the investment options sponsored by the recordkeeper. This same finding is something we have demonstrated in prior blog posts. This means that it is not meaningful to compare the recordkeeping fees of individual jumbo plans, particularly for the purpose of inferring fiduciary malpractice, because there are material differences in how fees are calculated. Specifically, you cannot compare the recordkeeping fees paid by jumbo plans without first identifying whether the plans have used the proprietary investments of the recordkeeper.

The following is an analysis of the key findings of the CEM jumbo-plan survey. We then apply the survey results to the pending excess fee case against Tyson Foods. In addition to the CEM proof that large-plan recordkeeping is not commoditized, we highlight additional issues that have become muddled in the defense of meritless excess fee lawsuits: (1) we cannot allow a meaningful benchmark in excess fee cases to constitute a few random plans – a benchmark is only meaningful if it involves a national survey that allows for comparisons to the median and mean of plan fees; and (2) comparisons of the services of a recordkeeper need to distinguish between transaction fees and recordkeeping services.

The CEM Benchmarking Study – Recordkeeping Fees Are Not Commoditized

The CEM study surveyed the recordkeeping fees for 123 plans with a plan average size of $6.4B and a median of $9.7B. The average number of participants was 39,412, with a mean of 83,493. The recordkeeping fees for these jumbo plans ranted from $20 to $80 per participant, with an average fee of $36. The survey involved the very largest defined contribution plans in America.

While not listed as a key finding, this study of over 100 jumbo plans revealed that recordkeeping fees ranged from $20 to $80, which CEM noted in and of itself “suggests that record keeping today in not a ‘commodity service.’” This is key premise of excess fee lawsuits that CEM debunks. For example, here are the numerous claims in the Tyson Foods excess fee case that asks a court to presume that large-plan recordkeeping is a commodity service:

- Paragraph 67: “nothing in the Tyson Foods Plan Fee Disclosure Notice to suggest that there is anything exceptional, unusual, or customized about the RKA services provided to Tyson Foods plan participants by Northwest.”

- Paragraph 68: “The Plan provided participants all commoditized and fungible RKA services provided to all other very large 401(k) plan participants. The quality or type of RKA services provided by competitor recordkeepers are comparable to that provided by Northwest.”

- Paragraph 69: “Any differences in these RKA services are immaterial to the price quoted by recordkeepers for such services.”

- Paragraph 70: “Given the fungibility and commoditization of these RKA services for massive plans like the Tyson Foods Plan.”

- Paragraph 72: “[I]ndustry experts have maintained that for massive retirement plans like the Tysons Foods plan, prudent fiduciaries treat Bundled RKA services as ‘a commodity with little variation in price.’”

- Paragraph 75: RKA services “are essentially fungible and the market for them is highly competitive.”

- Paragraph 76: “Given the mammoth size of the Tyson Foods Plan . . and the trend of price compression for RKA services over the last six years, it is possible to infer that Defendants did not engage in any competitive solicitations of RKA bids, or only ineffective ones, breaching the[i]r fiduciary duties of prudence.”

- Paragraph 78: Recordkeeping services are “fungible and commoditized”: Fidelity has “in fact conceded that the RKA services that it provides to other massive plans are fungible and commoditized, including plan services provided to its own employees.”

- These cookie-cutter commodity claims are in every single Walcheske complaint. They just cut and paste these statements into the next lawsuit. Nevertheless, a significant fee range of $20 to $80 for America’s largest plans demonstrates that there are large differentiations in the level and quality of services provided to jumbo defined contribution recordkeeping services.

The CEM study has four additional key findings:

- When the number of plan participants doubles, recordkeeping costs drop by 16%

- A 10% increase in the number of participants is associated with a 1.6% decrease in the cost per participant. Extrapolating this finding, when a plan doubles in participant count, the average recordkeeping cost increases by 16%.

- A large number of participants can spread the fixed costs associated with recordkeeping over a greater base. Consequently, larger plans benefit from lower recordkeeping costs per participant compared to smaller plans with fewer participants to distribute the fixed costs over.

- Recordkeeping fees are reduced by 13.3% when the plan uses the recordkeeper’s proprietary managed account service.

- The cost per participant goes down 18.2% when the plan uses the recordkeeper’s proprietary investment options in the plan.

- Higher account balances do not imply lower costs. In fact, plans with higher average holdings per participant tend to have higher recordkeeping costs.

The CEM Recordkeeping Fee Study proves that a key driver in lowering the price of recordkeeping fees is whether you include proprietary investments and/or the managed account platform of the recordkeeper – not larger account balances. The use of proprietary investments from the recordkeeper has a larger impact on lowering fees than even when the plan doubles in size. The size of the plan makes a difference, with a 16% difference between a $1B and $2B plan. But use of proprietary investments has a 18.2% impact. A $1b plan that uses the proprietary investments and managed account services of the recordkeeper will have a lower recordkeeping fee than a $2B plan that is double in size.

As we prove in detail below, if you apply this finding from the CEM study to the pending fiduciary breach case against Tyson Foods, you will find that plaintiffs are comparing plans with proprietary investments from the recordkeeper to the Tyson Foods plan without proprietary investments. It is an unfair comparison, and certainly not enough to infer a fiduciary breach to meet the “plausibility” pleading standard. Unless we are taking the position that it is a fiduciary breach under ERISA to exclude proprietary investments from the recordkeeper, then courts must reject any inference of fiduciary malpractice based on comparisons to a few random plans.

We note that the survey does not address other factors that explain disparities in recordkeeping fees, namely administrative complexity and service levels. Administrative complexity includes the complexity integrating payroll systems, and the impact of balance rollovers to retail brokerage accounts. Recordkeeping pricing is also influenced by negotiated service levels, including the number of personnel assigned to the account by the recordkeeper, and the number of one-on-one education sessions.

SPARK and the recordkeeper industry need to put out authoritative information like the CEM Study to debunk the plaintiff-lawyer premise that recordkeeping is a commodity. Until recordkeepers fight back, they are allowing their clients to be sued in frivolous fiduciary-breach litigation.

The Excess Recordkeeping Fee Case Against Tyson Foods

On November 11, 2023, Walcheske lawyer Paul Secunda filed an excess fee class action lawsuit alleging that the Tyson Foods plan fiduciaries failed to leverage the “mammoth size” of the $3.2B plan with 67,276 participants to timely negotiate lower fees from Northwest Plan Services, Inc. [The size of the plan changes every time it is mentioned in the successive complaints in the case, and it varies year-to-year, but the key fact is that Tyson Foods sponsors a jumbo plan with assets between $2.5 and $5b, and with over 50,000 in participants. It is a lot of participants, even for a jumbo-size plan, but the exact type of gigantic plan that was surveyed in the CEM study].

The Tyson Foods excess fee complaint alleged that the plan fiduciaries breached their fiduciary duties “by requiring the Plan to ‘pay [] excessive recordkeeping [and administrative RKA fees],’” and by “failing to remove a high-cost recordkeeper, Northwest Plan Services, Inc.” The complaint further quotes from the June 2023 participant fee disclosure that “[p]lan administrative expenses are charged monthly to [participants’] Plan account on a per capita basis based on expenses paid in that month. This means every participant in the plan is charged the same amount. The amounts charged to [participants’] account are based on the actual monthly expenses incurred by the plan for administrative fees. Based on the previous year’s expenses [participants] could expect an annual fee of $36 to $53. Since the fee charged to participants are based on actual expenses this estimate can change.” While plaintiffs had the participant fee disclosure revealing a lower $36 recordkeeping fee [plus additional plan administration costs charged to participants unrelated to recordkeeping], the complaint still declares that “[b]ased on Plan 5500 Forms between 2017 and 2022, Northwest in fact charged Plaintiffs and Class Members between $40 and $46 annually per year deducted quarterly per participant for Total RKA.”

Plaintiffs calculated fees from the Form 5500 despite the participants serving as class representatives having received fee disclosures and account statements that showed the exact amount charged each year – namely $36 for core recordkeeping fees. The quoted language from the fee disclosure is intended to reflect that participants are charged a fixed recordkeeping fee and an additional administrative fee to reimburse the plan sponsor for additional administrative costs in running the plan. The additional fee changes year-to-year based on the expenses incurred. But it is not a recordkeeping fee. This is a key issue that gets lost and muddled in excess fee cases.

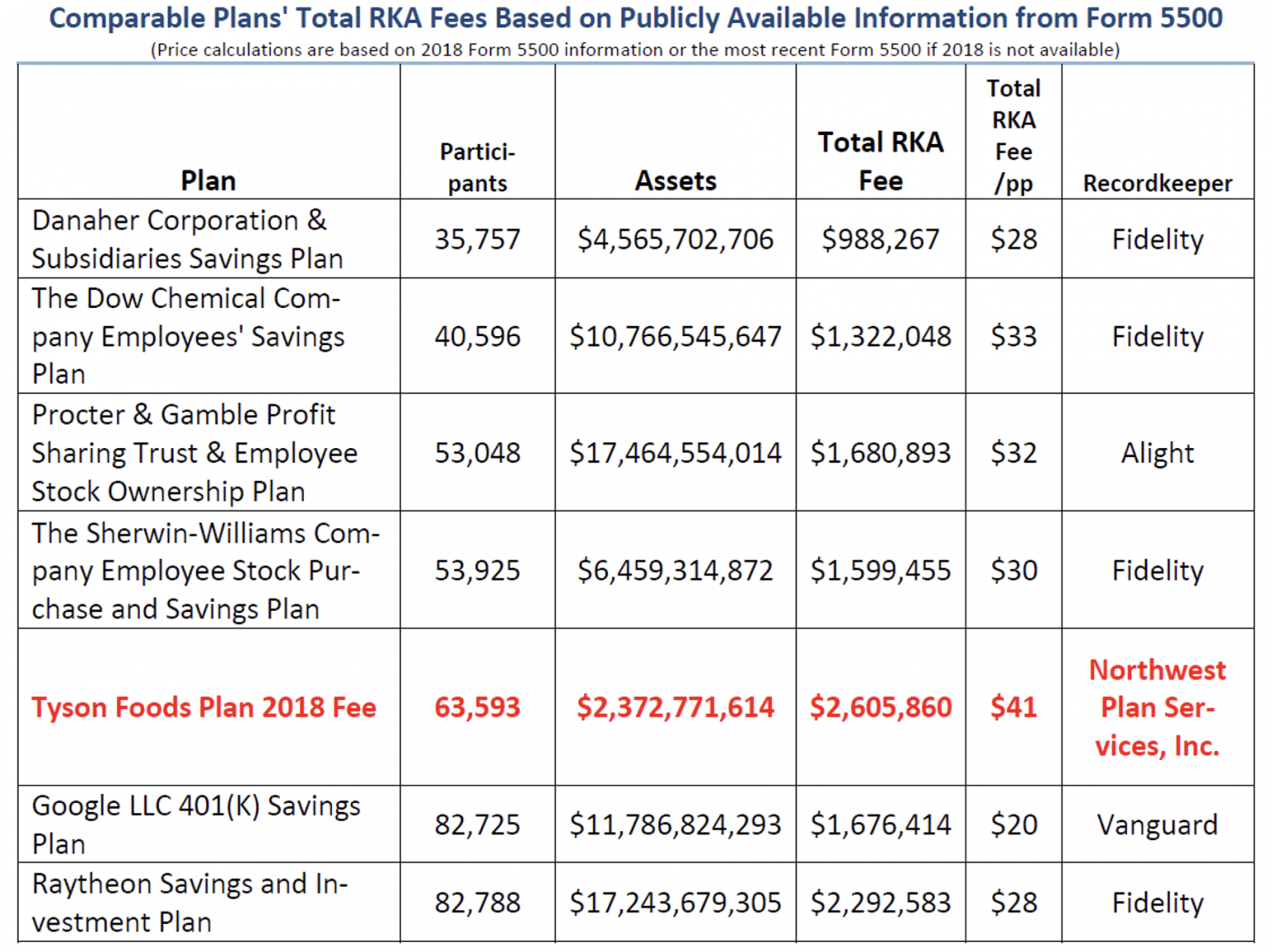

The Complaint compares the alleged $41 average fee for six years calculated from the Form 5500 against six other plans using 2018 numbers:

The complaint asserts that these six comparator plans establish a $28 reasonable fee compared to the $42 [instead of $41 in the comparator chart], creating “an unreasonable disparity of $18 per participant (over 75% premium).”

Tyson Foods filed a motion to dismiss the initial complaint. Tyson argued that Plaintiffs were improperly comparing the Tyson plan to fees of other plans that were materially different, because (1) the Tyson plan fees include additional plan administration fees unrelated to recordkeeping, and (2) the six purported comparison plans were not comparable to the Tyson plan because they had materially different numbers of participants and assets.

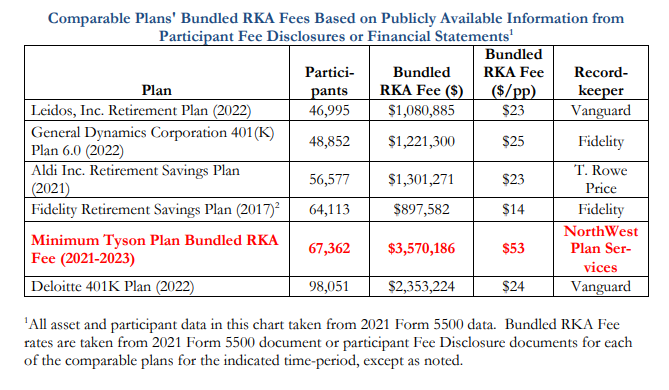

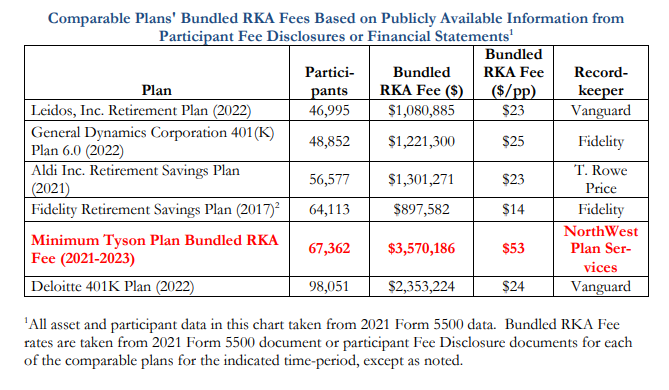

Plaintiffs filed an Amended Complaint on April 5, 2024 alleging the same claims, but changed the definition of universal RKA services that all plans supposedly receive. Plaintiffs also abandoned the prior “comparator” plans in favor of five new ones.

We would note that Tyson’s alleged recordkeeping fee ballooned from $41 to $53 from the original to the Amended Complaint. This demonstrates that nothing alleged in a fiduciary-breach excessive fee case should be taken as truthful.

Tyson Foods filed a new motion to dismiss. First, Tyson argued that, under Matousk v. Mid.-Am Energy Co., 51 F.4th 274, 278-80 (8th Cir. 2022), plaintiffs cannot state an excessive fee claim by pointing to a few “cherry-picked” plans that paid a lower recordkeeping fee and conclude that a plan’s “costs are too high.” Under the Mid-American meaningful benchmark requirement, “the way to plausibly plead a claim of this type is to identify similar plans offering the same services for less.” Specifically, plaintiffs’ $53 purported recordkeeping all-in number includes “legal, audit, custodial, investment management, plan communications, participant investment guidance, recordkeeping, document retention, administrative personnel and other administrative fees.” For the comparator plans, however, plaintiffs define “RKA” [RKA is Walcheske’s definition of recordkeeping and total plan administration costs] to not include “legal,” “audit,” “investment management,” and “participant investment guidance” services. As a result, plaintiffs’ allegations are comparing all fees paid by the Tyson plan for all the listed services against the alleged fees paid by the other plans for “only basic recordkeeping services.” It is apples versus oranges.

Second, Tyson argued that plaintiffs’ comparator plans do not represent a “like-for-like” comparison because they are not “comparably sized” to the Tyson plan, as required under the MidAmerican meaningful benchmark. Using participant size, those allegations show that one of the comparators has thousands fewer participants and the other four have differences in the tens of thousands. Most of the comparator plans were three times the size of the Tyson plan, and one other was six times bigger.

First Amended Complaint Dismissed Because (1) Comparators Did Not Plausibly Offer the Same Services and (2) Were Not the Same Size: The Western District of Arkansas federal court agreed with Tyson Foods and dismissed the case without prejudice. In dismissing the case, the Tyson court acknowledged that a higher pleading standard must be applied to ERISA recordkeeping-fee and imprudence investment claims: “plaintiffs . . . cannot ‘clear[] the pleading bar [except] by alleging enough facts to ‘infer . . . that the process was flawed.” Matousek v. Mid-American. “Such an inference is only plausible if the plaintiffs can point to “similarly sized plans [that] spend less on the same services.” Id. at 279 (citing Albert v. Oshkosh, 47 F.4th at 579-80) (emphasis added).

The court first agreed that the Tyson plan does not offer the same services as plaintiff’s comparator plans. Plaintiffs had admitted that Tyson may have been charged higher fees for extra services, and thus the comparator plans were not sound or meaningful benchmarks. Second, the comparator plans were not similarly sized to the Tyson plan. From the chart in the complaint, the Leidos ($10.0B), General Dynamics ($9.9B), and Deloitte ($9.9B) were nearly three times larger than the Tyson’s plan ($3.5B) in terms of asset size; the plan sponsored by Fidelity ($24.3B) is nearly seven times larger than Tyson’s; and the plan sponsored by Aldi ($1.6B) is less than half of Tyson’s size.

Plaintiffs argued that they had survived a motion to dismiss in the excess fee case against U.S. Bancorp (Dionicio v. U.S. Bancorp, 2024 WL 1216519 at *1, *31 (D. Minn. Mar. 21, 2024)) based on the same comparator plans. Plaintiffs argued that the District of Minnesota held that any mega plan with over $500 million in assets and at least 46,000 participants would serve as a fair comparator to any other mega plan. But the Tyson court held that the Dionicio court “did not issue a sweeping holding as to all mega plans.” Instead, the Tyson’s court held that the U.S. Bancorp case survived a motion to dismiss because three of the seven comparators were “very close” in asset size to the $10B-sized U.S. Bancorp plan. The three similar plans – sponsored by Leidos, General Dynamics, and Deloitte – contained assets ranging from $9.9 to $10.0B. In denying the motion to dismiss, the Dionicio court observed that these three comparator plans had a “difference in assets of less than 1%.” The court ruled that “having three good comparators is sufficient to state a plausible claim.”

ENCORE NOTE: As discussed more fully below, the decision in the U.S. Bancorp case allowing an excess recordkeeping case to proceed based on just three similarly-sized comparison plans is problematic and unfair. The Walcheske firm used the exact same plans in the U.S. Bancorp and Tyson Foods cases. The comparators are all misleading and not representative of what jumbo plans actually pay for recordkeeping. Leidos, General Dynamics and Deloitte pay a below-average recordkeeping fee. A below-average fee surely cannot be plausible proof from which to infer fiduciary imprudence. It may be possible proof, but not plausible proof. Moreover, the reason these three plans have a below-average recordkeeping appears to be because they all use the proprietary investments of the recordkeeper, whereas Tyson Foods did not. This is why the CEM study is valuable. Surely it is not evidence of fiduciary malpractice for Tyson to choose investments in its 401k plan that are independent of its recordkeeper!

Leave To a Second Amended Complaint: After the motion to dismiss of the First Amended Complaint was denied without prejudice, judgment was later entered by the court. We do not understand why this happened, because normally a dismissal without prejudice allows plaintiffs to file another complaint. Nevertheless, on August 13, 2024, plaintiffs filed for permission to file a Second Amended Complaint. The new complaint keeps the same original five comparators that the district court held were too dissimilar to serve as a meaningful benchmark, and then added four new comparators. Specifically, the Second Amended Complaint purports to “infer a flawed fiduciary process” based on the disparity of the fees in five comparator plans based on participant size [Leidos, Inc.; General Dynamics; Aldi Inc.; Fidelity; and Deloitte] and four new plans based on asset-size [IU Health; TJX Companies; Verizon; and RELX].

The following are three key points presented by the Second Amended Complaint in the Tyson Foods excess recordkeeping fee case:

KEY POINT #1: The comparators in the Tyson Foods excess fee case are not meaningful benchmarks because they purport to compare the Tyson plan without proprietary investments to plans with discounted recordkeeping fees because they use the proprietary funds of the recordkeeper.

The Walcheske law firm has now filed three separate complaints alleging the recordkeeping fee charged by Northwest to the Tyson plan was excessive based solely on comparisons to a handful of random plans. Tyson Foods has objected to the leave to file the second amended complaint on the grounds that the comparators do not meet the MidAmerican meaningful benchmark test because they are dissimilar in both asset and participant size to the Tyson plan. These are legitimate arguments. But if you apply the findings of the CEM recordkeeping study, there is a more fundamental reason why it is not fair or legitimate to compare the Tyson Foods plan to the Walcheske comparator plans: the Tyson Foods plan does not contain proprietary investments from its recordkeeper, but it is being compared to plans with discounted fees because they contain the proprietary investments of the recordkeeper.

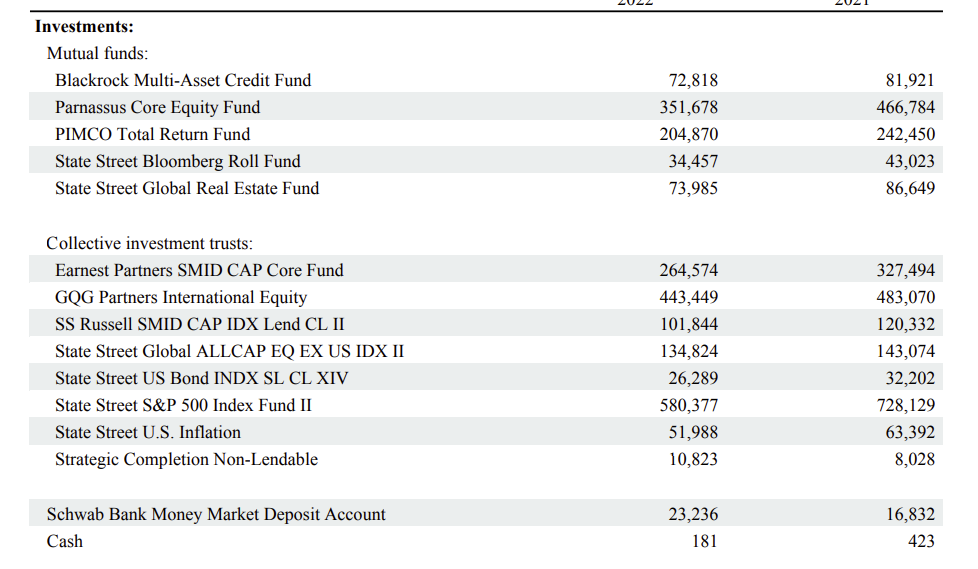

The following is a chart of the investments of the Tyson Foods plan that is taken from the plan financials attached to its publicly filed 2022 Form 5500:

You will note that the Tyson’s plan has no investment option that is proprietary to its recordkeeper Northwest. All of the investments are offered by independent investment companies, like State Street, BlackRock and PIMCO. We would note that the core offerings appear to be from State Street, which is a high-quality, low-cost investment provider. The State Street S&P 500 Index Fund is likely offered at one basis point – almost free. If we are going to allow inferences of process from fees and investments, you have to be fair to the fiduciaries of the Tyson Foods plan by inferring it has a prudent process that values low fees. Why? Because State Street index investments are always low cost. You have to infer that these plan fiduciaries who chose low-cost State Street index funds have sought to ensure the reasonableness of plan fees – the exact opposite of the false premise of the excess fee lawsuit that Tyson is forced to defend.

We cannot find investment information from Form 5500 public filings for all nine comparators in the Tyson Foods Second Amended Complaint. But each plan used by Walcheske to infer fiduciary imprudence that we can verify uses the recordkeeper’s proprietary target-date funds as the QDIA in the plan. Here are four examples:

- Leidos, Inc. Retirement Plan: Vanguard is the recordkeeper for the 46,995 participant/$9.8B plan, and over $3.5B of plan assets are invested in Vanguard investment products, including the plan QDIA in Vanguard target-date funds. Vanguard is the recordkeeper and offers the primary investments in the plan.

- Aldi Inc. Retirement Savings Plan: T. Rowe Price is the recordkeeper of the $1.46B plan, and well over 50% of the assets are in the TRP target-date funds and a TRP stable value fund.

- Deloitte: Vanguard is the recordkeeper and sponsors most of the plan investments: $8.2B plan with $7.4B in Vanguard TDFs and the mutual funds – almost all proprietary Vanguard investments.

- RELX: Empower is the recordkeeper for the 19,573/$3.5B plan. The Form 5500 discloses $952,241 in compensation for Empower’s Managed Account and Empower self-directed brokerage account. The plan uses Vanguard TDFs, but proprietary Empower managed account services.

When applying the findings of the CEM recordkeeping study, this analysis shows that is not fair or meaningful for Walcheske to compare plans with investments from the plan recordkeeper to the Tyson plan with no proprietary investments. Fees charged by recordkeeper vary based on service model and, as the CEM study proves, other factors like whether you use the proprietary investments from the recordkeeper. It is not proper to infer fiduciary malpractice if plan fiduciaries use their discretion to choose non-proprietary investments, even if that is the cheaper route. Unless we are going to impose fiduciary liability for failure to use the proprietary investments of the recordkeeper, which would be a perverse requirement, the comparator plans in the Tyson Second Amended Complaint are not meaningful benchmarks – certainly not meaningful enough to infer fiduciary imprudence. The CEM survey proves that variations in recordkeeping fees for jumbo plans are not plausible inference of malpractice.

KEY POINT #2: The pleading standard of a “meaningful benchmark” cannot allow a comparison to a few random plans.

The pleading standard for validating an ERISA excess fee case is supposed to be a higher level of scrutiny than other types of cases. Specifically, in Matousek v. MidAmerican Energy Company, the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals held that to survive a motion to dismiss for failure to state a claim in an excess fee case, plaintiffs must “identify similar plans offering the same services for less.” 51 F.4th at 279 (citing Albert v. Oshkosh Corp., 47 F.4th 570, 579-80 (7th Cir. 2022). A district court “cannot infer [a plan fiduciary’s] imprudence unless similarly sized plans spend less on the same services.” Id. at 279. Therefore, “[t]he key to nudging an inference of imprudence from possible to plausible is providing a sound basis for comparison – a meaningful benchmark – not just alleging that costs are too high or returns are too low.” Id. at 278.

But what does it mean to compare to “similarly sized plans”? Does that require a credible national survey that establishes a median and average recordkeeping fee, or is it enough to compare to a few random plans. ERISA defense lawyers appear to be conceding that plaintiffs can meet the higher plausibility pleading threshold by comparing to a few random plans. The U.S. Bancorp case shows how dangerous this is, when plaintiffs are allowed to challenge a low $29 recordkeeping fee based on comparisons to just three plans. The court only required that the plans be of a similar size. There is a slippery slope in the meaningful benchmark requirement if we allow a few random plans to serve as the benchmark.

Three comparators should not be plausible evidence sufficient to infer fiduciary imprudence. The CEM study shows how unfair that is. The study shows that mega plans have a wide variation in recordkeeping fees (and are thus not commoditized services), and that the #1 factor besides doubling in size to lower fees is use of recordkeeper’s proprietary investments. The CEM survey further proves that plaintiffs are misleading courts by using comparator plans that have a lower recordkeeping fee because the plans include proprietary investments and services from the recordkeeper. Thus any inference of fiduciary malpractice would be misplaced. The comparison would only show a preference to avoid proprietary investment products, which is usually a sign of prudence. In fact, the same plaintiff firms have filed many other cases alleging that proprietary investments are an inherent sign of imprudence.

Simply put, the meaningful benchmark in MidAmerican is not meaningful if you can plead a plausible case with a few comparator plans. The plan sponsor community must demand that a “meaningful” benchmark is only meaningful if compared to a credible national survey that shows the mean and median of whatever other plans pay for recordkeeping services.

KEY POINT #3: Comparison of Recordkeeping Fees Cannot Include Participant Transaction Fees or Other non-recordkeeping fees that plan sponsors charge through the recordkeeper.

The defense of so many excess fee cases has caused some issues to become muddled. Specifically, the defense of these cases has centered on comparing recordkeeping services in an apples-to-apples way. But some of these fees are not even recordkeeping. You should not even get to a comparison of recordkeeping “services” when the fees are for completely different plan administration services.

The Tyson Foods plan uses the recordkeeping platform to charge additional plan administration fees to plan participants. This a settlor decision that is entirely legitimate. But we cannot allow plaintiff law firms to include non-recordkeeping fees in comparisons to infer fiduciary imprudence. The Tyson federal court understood this distinction in the motion to dismiss decision, but it still left open the possibility of comparisons to just three plans of a similar size.

Some court consider this defense as a fact issue. But the fee charged to participants is not a fact issue. There is an objective truth of what the recordkeeping fee is in a defined contribution plan. It is not a fact dispute. It is a concrete amount. There may be variation when the fee is on a percentage-of-asset basis, or when revenue sharing is involved. But even then, the participant can access the fee paid in participant account statements. We cannot allow federal judges to claim that the objective truth of a fee amount is somehow a fact issue.

Similarly, we must insist that comparison of recordkeeping fees cannot include transaction fees. The focus on asking courts to require a comparison of recordkeeping services has unfortunately muddled this key point. The confusion is caused by the fact that some services are transaction fees that have nothing to do with recordkeeping. Form 5500 recordkeeping fee data sometimes includes participant transaction fees that are not core recordkeeping services. We must demand apples-to-apples comparisons of fee amounts, which means that transaction fees cannot be defined as recordkeeping services to mislead federal courts with manufactured fact issues.

FINAL THOUGHTS

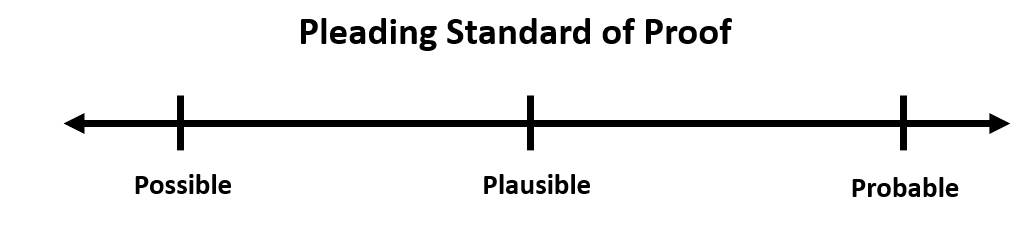

The inconsistent application of the pleading standard in federal courts continues to drive the litigation abuse in ERISA class action cases. The Tyson court correctly noted that a higher plausibility standard applies to excess recordkeeping and imprudent investment cases. In order for a fiduciary-breach complaint to survive a motion to dismiss, plaintiffs must allege plausible evidence to infer a flawed fiduciary process.

Our chart shows the difference in the pleading standards. A low pleading standard would be possible evidence of imprudence. The highest standard used in a criminal case would be require probable cause. ERISA class actions would be require proof somewhere in the middle with the requirement of “plausible” evidence.

If a plaintiff firm, like in the U.S. Bancorp case, finds three plans of a similar size with a lower recordkeeping fee, that might be POSSIBLE evidence that U.S. Bancorp has a flawed fiduciary process. But it cannot be PLAUSIBLE evidence that U.S. Bancorp has a flawed fiduciary process. Plausibility would require proof that U.S. Bancorp fees were well above the median and average of a reliable survey of jumbo plans. If a credible survey showed that the two companies had a recordkeeping fee that was in the 90th percentile, that might be plausible proof of a problem from which to infer imprudence. But without context and perspective of where the fees fall into the range of all plans, there is no plausible evidence.

Simply put, plausible evidence should require a national benchmark study. The CEM study reveals the unfairness of comparing random plans without the context of their investments. The plan sponsor community must demand a fair application of the pleading standard that requires credible proof. The current crapshoot standard is allowing rampant litigation abuse, like the excess fee cases against Tyson Foods and U.S. Bancorp.