By Daniel Aronowitz

The traditional formula of a fiduciary imprudence case for excess plan fees is to (1) allege a false recordkeeping fee based on inflated data from the Form 5500; and then (2) compare the false data to misleading and fake benchmarks from a handful of carefully selected plans that purportedly pay low recordkeeping fees. Most cases also allege that Fidelity has admitted to the world that its recordkeeping services are only worth $14 per plan participant. The Walcheske & Luzi and Capozzi Adler law firms specialize in this excess fee playbook. For years, these firms calculated the per-participant fee from the Form 5500, notwithstanding that each participant receives quarterly fee disclosures from the plan recordkeeper under Department of Labor rule 404a5. Participants also receive account statements with their account balance and fees paid. That has not stopped plaintiff lawyers from asserting fiduciary malpractice for excessive recordkeeping fees that are higher than what is recorded in 401k account statements and fee disclosures.

This traditional excess fee formula has not changed. But there has been a subtle change in recent excess fee cases, likely because plan sponsor advocates like the Fid Guru Blog have exposed the con game of the excess fee template that ignores participant fee disclosures and account statements. The change is that plaintiff law firms are now acknowledging that their participants receive quarterly fee disclosures with the recordkeeping amount clearly stated. That has not stopped the misrepresentations and misleading benchmarks, however, as excess fee complaints are still comparing challenged plans to random comparator plans with misleading data points from the Form 5500. Most importantly, the complaints fail to place the challenged plan fees into the overall context of what the majority of large plan sponsors actually pay for retirement plan recordkeeping services.

But there is a more critical issue that has not been identified by litigants in prior cases: many large plan sponsors charge an additional administration fee amount beyond just the standard fee paid to the plan recordkeeper for recordkeeping fees. These additional fees represent administration fees outside of the services from the recordkeeper, like legal and accounting fees incurred by the plan sponsor. They are not recordkeeping fees, but are often mischaracterized as recordkeeping fees in order to inflate the excess fee claim.

These additional administration fees are at issue in the latest excess fee case filed by the Walcheske law firm in Randall W. Ruebell v. Tyson Foods, Inc., W.D. Ark. (filed November 11, 2023), although you have to look closely because the plaintiff firm mischaracterizes these fees as standard recordkeeping (and then compares the inflated amount to recordkeeping fees from plans in which additional administrative fees are not charged to participants). In the November 11, 2023 complaint, Walcheske lawyer Paul Secunda alleges that the Tyson Foods plan fiduciaries failed to leverage the “mammoth size” of the $3.2B plan with 67,276 participants to timely negotiate lower fees from Northwest Plan Services, Inc.

The most specific flaw in the Tyson Foods excess fee case is that the complaint inflates the recordkeeper fee by including plan administration fees that do not constitute plan recordkeeping. The complaint then compares the recordkeeping and additional plan administration expenses against the pure recordkeeping fee amount of a few random plans. It is an apples to apples + oranges comparison.

It is useful to explore this key issue that many companies charge additional administration fees beyond just plan recordkeeping. Just because these additional fees are disclosed on the recordkeeper’s fee disclosure, it does not mean that it constitutes recordkeeping. And we do not believe it is a breach of fiduciary duty to charge additional fees to plan participants. This should be a settlor business decision. Nevertheless, this key nuance in plan administration has not been addressed in any of the cases we have seen to date. But it is a key distinction that defense lawyers need to expose to properly defend plan sponsors like Tyson Foods. We explore three key flaws in the fiduciary imprudence claims in the Tyson Foods case.

The Tyson Foods Excess Fee Case

The Tyson Foods excess fee complaint alleges that the plan fiduciaries breached their fiduciary duties “by requiring the Plan to ‘pay [] excessive recordkeeping [and administrative RKA fees],’” and by “failing to remove a high-cost recordkeeper, Northwest Plan Services, Inc.” The complaint further quotes from the June 2023 participant fee disclosure that “[p]lan administrative expenses are charged monthly to [participants’] Plan account on a per capita basis based on expenses paid in that month. This means every participant in the plan is charged the same amount. The amounts charged to [participants’] account are based on the actual monthly expenses incurred by the plan for administrative fees. Based on the previous year’s expenses [participants] could expect an annual fee of $36 to $53. Since the fee charged to participants are based on actual expenses this estimate can change.” But while plaintiffs had the participant fee disclosure, the complaint still declares that “[b]ased on Plan 5500 Forms between 2017 and 2022, Northwest in fact charged Plaintiffs and Class Members between $40 and $46 annually per year deducted quarterly per participant for Total RKA.”

EUCLID NOTE: Plaintiffs still did a calculation from the Form 5500 despite the participants serving as class representatives having received fee disclosures and account statements that showed the exact amount charged each year. The quoted language from the fee disclosure it intended to reflect that participants are charged a fixed recordkeeping fee and an additional administrative fee to reimburse the plan sponsor for additional administrative costs in running the plan. The additional fee changes year-to-year based on the expenses incurred. But it is not a recordkeeping fee.

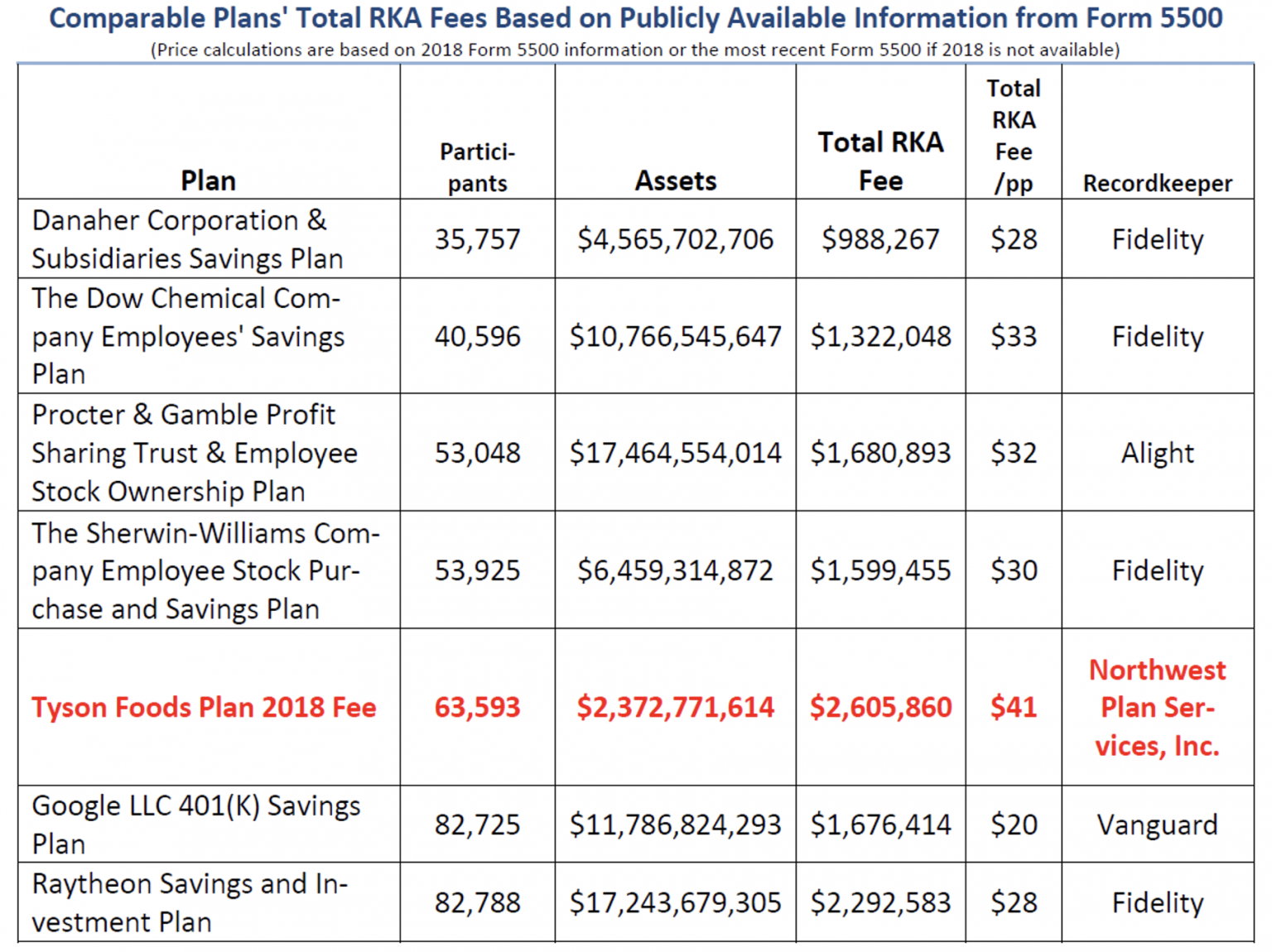

The Complaint compares the alleged $41 average fee for six years calculated from the Form 5500 against six other plans using 2018 numbers:

The complaint asserts that these six comparator plans establish a $28 reasonable fee compared to the $42 [instead of $41 in the comparator chart], creating “an unreasonable disparity of $18 per participant (over 75% premium).”

EUCLID NOTE: $42 minus $28 does not equal $18 (it equals $14). The math does not work.

Three Key Flaws to Debunk the Tyson Foods Excess Fee Imprudence Case

Flaw #1: Even if the Tyson Foods Recordkeeping Fee is $41-42, It Is Still Reasonable for $2B Asset Plans Based on the Euclid Recordkeeping Database.

The complaint attempts to compare the Tyson Foods plans to six other substantially larger plans. The comparator plans range from $4.5B to $17.5B – two to seven times larger than the $2.6B Tyson Foods plan. The argument in the complaint is that recordkeeping is based solely on the number of participants, and asset size has no relevance to the recordkeeping. But plaintiffs have no proof for this assertion, and it is wrong. Plaintiffs fail to provide any national average or median for what jumbo plans actually pay for recordkeeping services. Even if the recordkeeping fees for the six comparator plans are correct, however, these meager statistics are no basis from which to assume or speculate that most other jumbo plans pay the same fees.

The Euclid Recordkeeping database, with accurate and reliable recordkeeping fees from rule 408b2 plan fee disclosures of over 2,500 plans with over $100m in assets, demonstrates that the Tyson Foods recordkeeping fee alleged in the complaint is reasonable. Unlike the complaint with six random plans with unreliable statistics from the Form 5500, which is not designed to disclose what individual participants are charged for recordkeeping services, the Euclid database is a reliable gauge of what the majority of retirements plans pay at various asset sizes. While our database begins with 2020 statistics, and the complaint uses 2018 Form 5500 data, it still provides an average and median for jumbo plans that is more credible than the complaint.

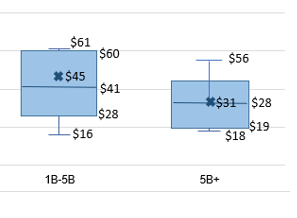

2020 Recordkeeping Fee by Plan Asset Size

SOURCE: Euclid Fiduciary 2020-2022 Recordkeeping Benchmark Survey

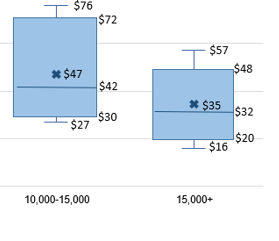

2020 Recordkeeping Fee by Plan Participant Size

SOURCE: Euclid Fiduciary 2020-2022 Recordkeeping Benchmark Survey

The Euclid Recordkeeping database shows that 80% of all plans with assets between $1B and $5B had recordkeeping fees between $28 and $60 with an average of $41 and a median of $45. The fees for 2018 plans were even higher than the 2020 data. If you look just at participant count, the Euclid database shows that 80% of all plans with 15,000 participants or more had recordkeeping fees between $20 and $48, with an average of $32 and a median of $35 per participant.

This data shows that higher-participant plans do pay less, but it still confirms that the Tyson Foods $42 recordkeeping fee is well within the normal range for jumbo plans. We are not conceding that Tyson Foods participants paid $42 in recordkeeping fees, as proven below. But even if the fee is $42, it is not evidence of fiduciary imprudence for failure to leverage the mammoth size of the plan in negotiating recordkeeping fees. $42 is consistent with both the average and median of mega plans between $1B and $5B.

Flaw #2: The Fees Labeled as “Recordkeeping” Include Plan Administration Fees.

The second flaw in the complaint is that its definition of “RKA” recordkeeping services includes plan administrative fees that are not recordkeeping, and even includes some accounting and legal services that are not even paid to the recordkeeper. This expansive definition of recordkeeping allows plaintiffs to inflate the recordkeeping fee paid by Tyson Foods participants, and then compares it to six random plans in which the recordkeeping fee does not include the extraneous, non-recordkeeping fees. It is an apples + oranges comparison to just apples.

The complaint alleges that “[t]here are three types of RKA services provided by all recordkeepers:

- The first type is labeled as “Bundled RKA,” which includes: recordkeeping; transaction processing; participant communications; maintenance of an employer stock fund; plan document services; plan consulting or investment management services to assist participants in selecting the investments offered to participants; accounting, audit and legal services, including the preparation of annual reports, like the Form 5500; compliance support; compliance testing; and trustee/custodian services.

- The second type of “essential RKA services,” which the complaint refers to as “A La Carte services,” represent “separate, additional fees based on the conduct of individual participants and the usage of the service by individual participants. These A La Carte Services include loan processing (at $35 for each occurrence), brokerage account services and account maintenance, distribution services, and processing of Qualified Domestic Relations Orders (QDROs).

- The third type of RKA fees are Ad Hoc transaction and other administrative fees, including ESOP fees, fees for service, and terminated maintenance fees.

The complaint alleges that the sum of the (1) Bundled RKA fees, (2) A La Carte RKA fees, and (3) Ad Hoc RKA fees = “Total RKA Fees.”

The first category of RKA services includes accounting and legal services that are likely not paid to the recordkeeper. This category is overbroad if the goal is to allege excessive recordkeeping fees. But the most egregious problem with plaintiff’s expansive RKA definition is the A La Carte services category. These are optional transaction services that are incurred by individual participants for individual transactions. The fees for loans and QDROs are not recordkeeping services. These transaction fee amounts are included in the Form 5500 as compensation to the recordkeeper, but they are not relevant to the recordkeeping fee that plaintiffs are alleging is excessive and proof of malpractice.

The complaint quotes from the Tyson Foods Plan Fee Disclosure dated June 30, 2023. It characterizes it as “boilerplate language” in every Northwest fee disclosure that “[p]lan administrative fees may include legal, audit, custodial, investment management, plan communications, participant investment guidance, recordkeeping, document retention, administrative personnel and other administrative fees.” Plaintiffs attempt to characterize this as the definition of recordkeeping services, but that is not correct. This summary – boilerplate or not – characterizes administrative fees that are beyond mere recordkeeping services. A claim of excess recordkeeping fees cannot include fees that do not constitute recordkeeping.

Flaw #3: The Purported Recordkeeping Fee of $42 With Additional Plan Administration Fees is Being Compared to Random Plans with Pure Recordkeeping Fees.

The six plans in the comparator chart with purported recordkeeping fees between $20 and $33 are derived from an aggregate fee amount from the Form 5500. The Form 5500 does not provide reliable data to calculate per-participant fees, because it contains fee paid by individual participants for non-recordkeeping services. In addition, plan sponsors do not uniformly record their recordkeeping fees on the Form 5500. Some plans include indirect revenue sharing amounts. Most include transaction fees like the loan and QDRO fees that the complaint characterizes as A La Carte services. But some plan sponsors only record the specific recordkeeping fees without transaction fees. This is a minority of plan sponsors, but the disparity prevents a meaningful comparison of data from one Form 5500 to another. The six plans in the comparator chart in the Tyson Foods complaint appear to just record recordkeeping fees – without transaction or other fees that inflate the statistics recorded in the recordkeeping box on the Form 5500 for most plans.

Why does this matter? Because plaintiff law firms have found six plans that have an artificially lower recordkeeping fee aggregate number than most large plans. This allows them to compare a plan like Tyson Foods that includes transaction fees in the Form 5500 to six plans that only record the actual recordkeeping fees. That means that the comparison is apples (recordkeeping fee) + oranges (transaction fees) to just apples (recordkeeping fee). It is not a fair comparison. The only fair comparison would be recordkeeping fees to recordkeeping fees. This is a flaw in nearly every excess recordkeeping fee case.

The Euclid recordkeeping database, without the distortions of transaction fees, gives a more credible viewpoint as to what $2.5B plans actually pay for recordkeeping. And its shows that a $41-42 per participant recordkeeping fee is well within the range of what other similarly sized plans pay. The Tyson Foods fiduciary imprudence claim is based on misleading and biased data. No fiduciary should be charged with fiduciary malpractice based on misleading and biased data. But this is what happens in excess fee recordkeeping cases.

The Euclid Perspective

On November 6, 2023, the Capozzi Adler law firm filed a fiduciary imprudence case against Whole Foods in Winkleman v. Whole Foods Market. Plaintiffs in that case alleged that the Whole Foods plan fiduciaries acted imprudently by paying a $31 recordkeeping fee to Fidelity. The complaint compared the $1.9B plan to seven random, but much larger plans purportedly paying between $10 and $27 per participant for recordkeeping services. In the Tyson Foods case, the Walcheske law firm has asserted fiduciary imprudence claims with a comparison chart of plans with five of the six mega plans purportedly paying close to the $31 per participant fee of the Whole Foods plan. If the Tyson Foods comparator chart can be believed, the Walcheske law firm has debunked the Capozzi Adler excess fee case against Whole Foods by alleging that jumbo plans pay approximate $30 per participant. It shows how arbitrary and capricious these excessive recordkeeping fee cases remain, and how the random-plan benchmarks are not reliable. The plaintiff benchmarks are based on flimsy and dubious data with no authoritative value.

Fiduciary imprudence is a serious claim. To be plausible, a fiduciary imprudence claim must be based on authoritative data. Despite years and hundreds of lawsuits, plaintiff lawyers still have no national database to support their fiduciary imprudence claims that large retirement plans pay the artificially low amounts asserted in the lawsuits. Even if they legitimately found the five to six lowest fee plans in America, it is not evidence of malpractice. They have no proof of what the vast majority of large plans pay for recordkeeping services. By contrast, Euclid’s Recordkeeping Database provides authoritative data proving that most of these lawsuits lack merit. That includes the recent lawsuits against Whole Foods and Tyson Foods.

Disclaimer: The Fid Guru Blog is intended to provide fiduciary thought leadership and advocacy for the plan sponsor community in areas of complex fiduciary litigation. The views expressed on The Fid Guru Blog are exclusively those of the author, and all of the content has been created solely in the author’s individual capacity. It is not affiliated with any other company, and is not intended to represent the views or positions of any policyholder of Euclid Fiduciary, or any insurance company to which Euclid Fiduciary is affiliated. Quotations from this site should credit The Fid Guru Blog. However, this site may not be quoted in any legal brief or any other document to be filed with any Court unless the author has given his written consent in advance. This blog does not intend to provide legal advice. You should consult your own attorney in connection with matters affecting your legal interests.