By Daniel Aronowitz

KEY POINTS: (1) A $31 Recordkeeping Per-Participant Fee is Well Below the Average and Median for $1B+ Asset Plans. But plaintiff law firms continue to file fiduciary malpractice claims with intentionally false comparators that are designed to fool federal judges into believing that jumbo retirement plans pay below $20 per participant.

(2) The plan sponsor community must fight back against frivolous excess fee lawsuits by publishing studies of what large plans actually pay for recordkeeping services and explaining how these services are differentiated by quality and scope.

The Capozzi Adler law firm has resumed its target practice on corporate America. This time it accuses Whole Foods of fiduciary imprudence by allowing Fidelity to charge excessive recordkeeping fees in the amount of $31 per participant to over 90,000 plan participants. See Winkelman v. Whole Foods Market, Inc. filed on November 6, 2023 in the Austin Division of Western District of Texas. Plaintiff admit that they know nothing about the fiduciary process of the Whole Foods fiduciary committee, and instead infer fiduciary imprudence based on comparing the Whole Foods $31 recordkeeping fee to: (1) the $14 per participant that Fidelity supposedly admitted is the fair value for its services to jumbo plans; and (2) unverified recordkeeping fees purportedly paid by seven random jumbo-sized plans with significantly larger assets.

The comparators are contrived and do not prove fiduciary malpractice. Nearly every jumbo plan, including plans with over $20B in assets, pays more than $14 per participant. In fact, the vast majority of jumbo plans with $1B or more in assets pay more than the $31 that Whole Foods pay for recordkeeping services. Euclid Fiduciary’s recordkeeping survey confirms that $31 is below both the average and median for $1B asset plans, which is at least $42 per participant. By contrast, the aggregate recordkeeping data for comparator plans in the complaint taken from Form 5500 filings of the seven large-company sponsored plans is not reliable. The reason is because Form 5500 numbers from which Capozzi Adler derives its false excess fee allegations are not accurate representations of what participants actually pay. The Form 5500 does not ask plan sponsors to represent what participants pay – that is what the rule 408b2 plan and 404a5 participant fee disclosures provide. Consequently, the assertion that Whole Foods has breached its fiduciary duties by failing to ensure reasonable costs represents another chapter in the con game of excess fee cases. The Whole Foods plan is just another in a long line of plans with extraordinarily low recordkeeping and investment fees that has been improperly sued for excess fees.

The Whole Foods 401k Plan Offers Super Low Investment Fees to Plan Participants

The Whole Foods plan in 2021 had 97,447 participants and over $1.9B in assets. Based on outdated statistics from the BrightScope/ICI Defined Contribution 2019 study, there are 776 plans with over $1 billion in assets under management. And the Whole Foods plan with over 90,000 participants is one of only 125 defined contribution plans with over 50,000 participants. The lead plaintiff Shauna Winkelman allegedly invested in the Fidelity Contrafund and the Vanguard 2050 target date fund. Three of the other six plaintiffs in the case, Kalea Nixon, Robert Goldorazena, and Chad Diehl, invested exclusively in the 2050 Vanguard target date fund. The complaint does not say how much they have invested in the plan, so you can assume it is a nominal amount.

The Complaint in paragraph 11 alleges that “Defendants . . . did not try to reduce the Plan’s expenses to ensure they were prudent.” But there is no proof for this speculation, and the complaint leaves out the total picture of the plan expenses to give full context and perspective. If you pull the 2021 Form 5500 for the Whole Foods plan, you will see that the Whole Foods plan offers a QDIA with the lowest possible share class of the Vanguard target date index funds at the miniscule fee of .04%. The four-basis point fee is the lowest that we have seen in any plan, and one-half of a basis point lower than the customary 4.5 basis point fee for the largest plans in America. If you try to invest in these same Vanguard funds on your own, you will pay 13 bps or higher. Many smaller plans have to pay anywhere from 9-13 bps for the same exact investment. The Whole Foods fiduciaries have leveraged their size to ensure low fees for its participants.

The plan’s low fees are proven with simple math. The plan has a $20,000 approximate average account balance. For a participant with a $20,000 average account balance that is invested solely in the Vanguard 2050 target date fund like three of the plaintiff participants, the investment fees would be .0004 x $20,000, or only $8. That means that these lucky participants pay a total of $39 total for all-in plan fees, if you include the $31 annual recordkeeping fee. A $39 all-in plan fee for the $20,000 average account balance should end any discussion as to whether the plan fees are reasonable. Try looking up your company’s retirement plan and see if you can invest $20,000 in the plan’s QDIA for just $38 in annual expenses. You cannot do it unless you are in a jumbo plan that leverages its size to reduce fees. This is exactly what the Whole Foods plan fiduciaries did. And it is why it is a farce that a plaintiff law firm has accused the plan fiduciaries of imprudence for failing to leverage the size of the plan to ensure reasonable plan fees.

If we are going to rely on just circumstantial evidence [like the complaint does] to judge fiduciary process, the 4 bps target-date fund investment fee belies the complaint’s premise that the plan fiduciaries were not cost conscious and failed to ensure reasonable plan expenses. Stated in the affirmative, the four bps fee is prima facie evidence that the Whole Foods fiduciaries have leveraged their size to ensure the lowest possible fees for plan participants. There is no basis from which to assume or imply that fiduciaries that negotiated the lowest possible investment fee from Vanguard would somehow overpay Fidelity for recordkeeping services.

The Capozzi Fidelity and Random-Plan Benchmarks Are False

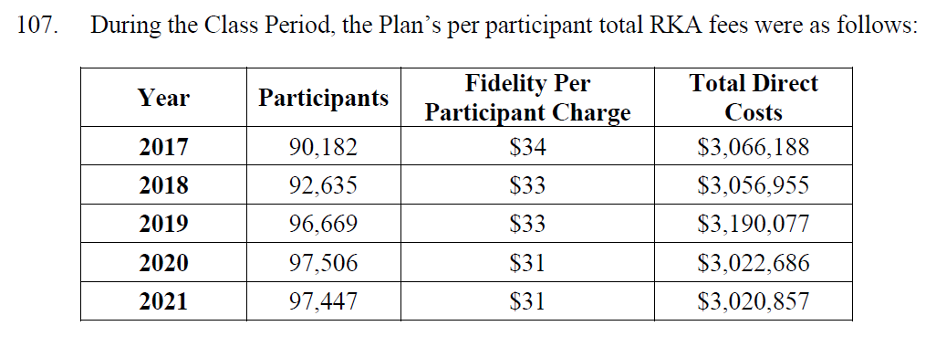

Most Capozzi Adler excessive fee lawsuits allege fiduciary imprudence based on inaccurate recordkeeping fees and then compare the purported inaccurate fee amounts to false and misleading benchmarks. This case is different to the extent that Capozzi Adler alleges accurate recordkeeping fees that are derived from company sources. The complaint admits that the Whole Foods plan lowered recordkeeping fees from $34 to $31 per participant over several years:

Even though Capozzi Adler has uncharacteristically alleged accurate recordkeeping fees, the firm nevertheless follows its customary playbook of comparing the $31 recordkeeping fee to false benchmarks in order to deceive the factfinder into believing that this is evidence of fiduciary malpractice. Capozzi normally miscites the fees from the 401k Averages Book, but this time the law firm went right to its disingenuous claim that Fidelity in the Moitoso v. FMR lawsuit admitted that the fair value of its recordkeeping services for large plans is between $14 and $21.

False Benchmark #1: The Fidelity $14 Benchmark is False and Disingenuous

The complaint alleges that “[t]he Plan should have been able to obtain per participant recordkeeping fees of at least $14 especially from Fidelity.” This is a tired argument that has been rejected by several courts, but it does not stop law firms from attempting to use the Fidelity discovery stipulation in the Moitoso v. FMR LLC case. Fidelity, through its lawyers at Goodwin Procter LLP, did sign a discovery stipulation of fact on May 1, 2019 stating that its recordkeeping services to its own employees participating in Fidelity’s internal 401k plan were worth $14 in 2017 and $21 in 2014. The stipulation said that these amounts would be the “arms-length” negotiated amounts, and that the services were no “broader or more valuable” than the services that Fidelity provides to $1B+ asset plans. But Capozzi leaves out the crucial qualifier that the stipulation “was offered for the purposes of the above-captioned litigation only, and [the parties] agree that they will not contest the validity of the stipulations in the context of this litigation only.” Shortly thereafter, on March 1, 2021 in Harmon v. Shell Oil Company, Case No. 3:20-cv-00021 (S.D. Tex), Shell lawyers at Skadden Arps filed a responsive statement that was signed by Goodwin Procter lawyer Alison V. Douglas, who signed the original Fidelity stipulation in the Moitoso case. This filing on behalf of Fidelity asserted that it does not concede that its recordkeeping services for $1B+ plans are worth only $14-21, because “the stipulation [in the Moitoso case] should not be considered to support Plaintiffs’ allegations in this case because it was expressly entered into for the limited purpose of resolving a discovery dispute in Moitoso.” Fidelity continued that the discovery stipulation in the Moitoso case “reflected a compromise between the parties,” and “is not relevant to allegations in this or any other case, and it certainly does not reflect the value of the recordkeeping services that Fidelity provides to different plans pursuant to different recordkeeping contracts for a different set of services.”

Capozzi Adler knows that the use of the Fidelity discovery stipulation is disingenuous. But their business model of manufacturing fake excessive fee imprudence claims is not about credibility. And it has nothing to do with helping participants. After all, this is a case about comparing a $31 annual fee to a $14 annual fee. Even if Capozzi is right and participants could have saved $17 on their annual recordkeeping fees, this is an immaterial amount, especially when most cases settle at 10-30% of the damages model. At best, this case is about recovering $17 per participant. This is a lawyer-contrived case that is only valuable for the one-third percentage of attorney fees that Capozzi can leverage if they can get past a motion to dismiss. They just need enough disingenuous and misleading comparators to mislead a federal judge into believing that Fidelity somehow overcharged Whole Foods by over 100%.

Goodwin Procter lawyers made what appears – at least in hindsight – to be a serious mistake in the Fidelity discovery stipulation given its unanticipated consequences. They need to figure out with Fidelity how to fix this mess and put the genie back into the bottle. It is costing plan sponsors and fiduciary insurers millions of dollars to defend cases based on the improper use of this stipulation. But no credible factfinder should allow plaintiff lawyers to file cases based on this discovery stipulation. We need federal judges to tell plaintiff lawyers to stop this nonsense. The credibility of the judicial system depends on lawyers to be honest. Instead of allowing disingenuous “gotcha” evidence, Capozzi Adler lawyers should be forced to provide a survey that shows that the average or median of recordkeeping fees of jumbo plans is less than $31. They cannot do this, because it would show that their entire claim is fabricated and fake. As shown below, this is because most jumbo plans pay more than Whole Foods plan participants.

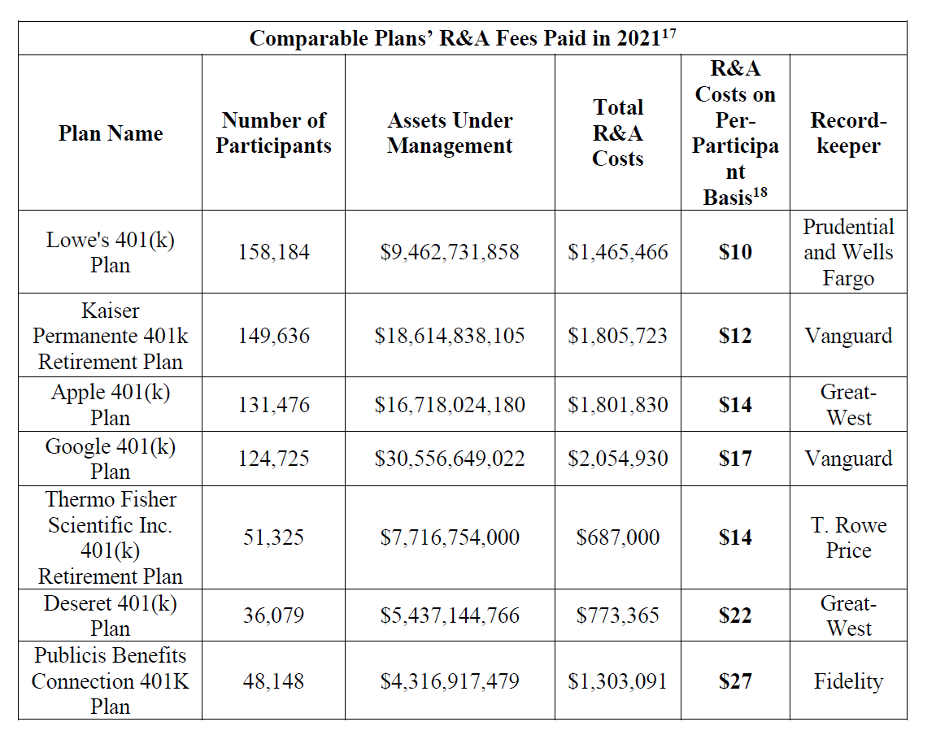

False Benchmark #2: Jumbo Plans with $4B to $30B in Assets are Not Reliable and Or Fair Comparators for the Smaller $2B Whole Foods Plan.

Instead of a reliable national survey of plans to provide proper context of what large plan participants pay for recordkeeping, Plaintiffs have chosen seven random, much larger, plans to assert that all high-participant plans have per-participant fees between $10-27. Try an analogy to home runs in the 2023 Major League Baseball season. Only five players had more than 40 home runs in 2023. If you compared these five players to a random player with only five home runs, you could conclude that the player was a bad home run hitter. But it is not fair to compare a random hitter to the top-five home run hitters in the league. In order to properly understand whether the hitter with five home runs was a poor hitter, you would need the average and median home run total of MLB hitters in order to evaluate how the player ranked. Needless to say, the average is well below than five home runs per player in a league with approximately 945 players.

This unfair comparison to the top players is exactly what excess recordkeeping fee cases attempt with the random comparator chart of the lowest fee plans that they can find. The prejudice is exacerbated, however, because these seven random plans are not a reliable indicator of what large plans pay for at least two other reasons: (1) the Form 5500 is not a reliable source of what participants pay for recordkeeping services [and is not intended for that purpose], and thus the amounts for each plan on the comparator chart are likely wrong; and (2) the comparator chart of $4B+ to $30B+ asset plans contain plans that are two to fifteen times larger than the Whole Foods sub-$2B plan, and that is why their fees might be lower.

First, the complaint states that the purported recordkeeping fees are taken from the Form 5500. The Form 5500 is not an accurate source for the per-participant fee charge to participants and is not intended for that purpose. Instead, it provides an aggregate amount of compensation paid to the recordkeeper, which includes transaction fees. Capozzi admits in footnotes 17 and 18 that the Form 5500 contains revenue sharing that might be credited back to participants. But they miss the more crucial distinction that Form 5500 aggregate compensation data includes transaction fees that are not representative of recordkeeping paid by participants. Capozzi asserts that this means that the Form 5500 number is inflated and thus the actual recordkeeping fees are likely lower for the seven plans on its comparator chart. That is the correct result for most plans, and why the recordkeeping fees asserted in most excess fee cases filed by the Capozzi law firm based on the Form 5500 are not reliable and false. [Capozzi plays “I gotcha” with Fidelity, so we hope defense firms will use this Capozzi admission against them in every case in which they assert excess recordkeeping based on the unreliable Form 5500 that overstates recordkeeping fees.] But the key point omitted from the complaint is that plan sponsors do not record compensation paid to the recordkeeper on the Form 5500 in a consistent manner. That is why plaintiff law firms have been able to find a few random plans with compensation paid to recordkeepers that is lower when divided by the number of participants than what is actually paid on a per participant basis. Because the Form 5500 is not recorded on a per-participant basis, it cannot be used as reliable evidence of what participants actually pay for each plan. It is certainly not reliable evidence from which to base serious claims of fiduciary malpractice. This is particularly true when plaintiff firms represent participants who have been given regulator-required fee disclosures under rule 404a5 that have the correct amount.

Given that they are based on unreliable sources, the purported fees on the comparator chart are likely wrong. We have seen fee disclosures for many of the plans on the comparator chart, and some of the recordkeeping fees for the cited plans are just plain wrong. As noted above, any evidence of recordkeeping fees from the Form 5500 is suspect. The Form 5500 provides aggregate compensation, and not the per-participant fees. It is possible to calculate the actual per-participant recordkeeping fee for a few plans, but not for the majority of plans. Any use of the Form 5500 for per-participant fees is suspect and not reliable. Plaintiff law firms know that the federal rules are used to presume that anything they allege is “true” for purposes of the motion to dismiss, but the track record of dishonesty in excess fee pleadings has proven that no plaintiff law firm with a profit motive is entitled to any presumption of truth when using false and misleading comparator plan data. This is especially true when every plaintiff-participant being used by plaintiff law firms has received a quarterly rule 404a5 fee disclosure with accurate data on the per-participant amount paid by participant.

Second, the purported fees are from plans that are at least two to fifteen times larger than the Whole Foods plan.

The complaint alleges that recordkeeping is based on number of participants and not assets, and that it is no more expensive to provide recordkeeping services for higher participant account balances or plan assets. There may be cost savings for higher account balances, but there is no proof that a plan with $30B in assets can secure a per-participant recordkeeping fee at the same rate as a sub-$2B plan. Euclid’s recordkeeping database shows the opposite. Our recordkeeping tracking shows that a larger asset plan has higher chance of a lower per-participant fee when compared to a lower asset plan. This is contrary to the premise of the lawsuit. Even if the recordkeeping fees of the seven plans in the Capozzi recordkeeping chart are correct – and we have proof that several of the plans have much higher recordkeeping fees – they are not fair comparators to the much smaller Whole Foods plan. To the extent that the fees are lower, it is because it is possible to leverage the much larger size. There is no proof that there is an ability to leverage a higher participant count that serves as the speculative premise of fiduciary imprudence in the Whole Foods excess fee complaint. Higher asset plans have lower, not higher, recordkeeping fees compared to small plans.

Based on our research and database, Vanguard is often cheaper than Fidelity for recordkeeping services, especially if the plan offers Vanguard target-date funds as the QDIA. Vanguard and Empower have a fraction of Fidelity’ market share, and that is because Fidelity is the best recordkeeper with the best technology. From our research, the only way most competitors will win large-plan business is to quote a lower price. The comparator chart reflects some of this competition against Fidelity. But that does not mean it is imprudent to choose a higher price to contract with the best company. And it is also why you cannot compare Empower plans like Apple or a Vanguard plan like Google to a Fidelity plan like Whole Foods, even if the plans were the same size and had the same scope of services.

Finally, it is important not to lose perspective that the complaint fails to give the average or median for the 750+ jumbo plans in America. The only comparators shown are the lowest fee plans that Capozzi Adler can find [although the fees represented are likely incorrect]. But the lowest plan fees are not proxies for what the average plan pays. As we show below, even if Capozzi Adler has legitimately found seven super-jumbo plans with the lowest fees in America, it is not evidence of fiduciary imprudence if the average paid by plans similar in size to the $1.9B Whole Foods plan is much higher.

$31 is a Below Average Recordkeeping Fee for $1B Plans with a High Number of Participants

Euclid Fiduciary has conducted a comprehensive survey of what large plans pay for recordkeeping services. Our survey includes accurate recordkeeping fees paid from 2020-2022 for a significant portion of the $1B+ plans in America. Our findings are available for any plan sponsor that wants perspective as to whether their plans are paying a fair and reasonable recordkeeping fee. Our database is also available to debunk the type of excess fee complaint against Whole Foods purporting to assert that a $31 recordkeeping fee was excessive by $17 per participant.

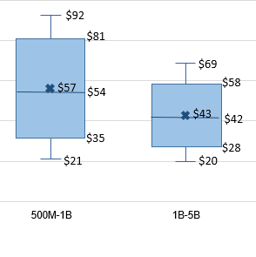

The Euclid Fiduciary database shows that in 2021, the year at issue in the Whole Foods complaint, 90% of all plans between $500m and $1B in assets paid more than $35 per participant, and the average paid by participants was $54, with a median of $57. For plans with assets between $1B and $5B, 90 percent of all plans had a per-participant fee of over $28 per participant. The average was $42 and the median for all such plans was $43. This means that the Whole Foods recordkeeping fee was lower than nearly every $1B plan, and well below the average and median for similarly sized plans.

2021 Recordkeeping Fee by Plan Asset Size

SOURCE: Euclid Fiduciary 2020-2022 Recordkeeping Benchmark Survey

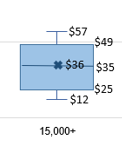

When measured on a participant basis, the Euclid Fiduciary database confirms that 90% of all plans with over 15,000 participants have per-participant recordkeeping fees over $25, with the average at $35 and the median at $36.

2021 Recordkeeping Fee by Plan Participant Size

SOURCE: Euclid Fiduciary 2020-2022 Recordkeeping Benchmark Survey

No matter how you compare it to a legitimate benchmark study, the Whole Foods $31 recordkeeping fee is reasonable, and well below the average of comparably sized plans. The Whole Foods $31 recordkeeping fee is lower than the vast majority of other jumbo plans in America. The fiduciary imprudence complaint is a frivolous, lawyer-driven lawsuit filed by a law firm that specializes in a business model of harassing corporate America.

Final Note: While this analysis is focused on the unreliable and unfair benchmarks of the Whole Foods excess fee complaint, we are by no means conceding the premise of the plaintiffs’ bar that all recordkeeping services are a fungible commodity. Like many services, including legal services and even professional liability insurance services that we provide, the services may be similar, but there are tangible differences in quality and scope. Recordkeeping is no different. The obvious differences are the scope of participant education and communication, whether onsite or how much is dedicated to a particular plan. The SPARK Institute and recordkeepers need to make this case publicly to stop the argument that all recordkeeping is a commodity. Service quality also matters, including systems and cybersecurity. Without fighting back, we are letting the plaintiff’s bar define and exploit the issue for financial gain.

The Euclid Perspective

Whole Foods will now have to spend millions of dollars defending its fiduciary process for a $31 recordkeeping fee. Its defense will likely cost more than the three million annual amount that it spends on what is a well below average recordkeeping fee. The plan sponsor community must publish accurate information demonstrating what plan sponsors actually pay for recordkeeping and how the quality and level of services are differentiated for recordkeeping. Since we cannot rely on federal courts to weed out frivolous cases on a consistent basis with the current variable pleading standard, we must take action to stop frivolous litigation based on false claims. For our part, Euclid has developed a comprehensive benchmark survey of what large plans actually pay for recordkeeping services. Our survey will be published soon and is available now for any plan sponsor or advisor that contacts us. The Euclid Fiduciary benchmark study will provide reliable proof that a $31 recordkeeping fee is below the average and median for $1B+ jumbo plans in America. Unless plan sponsors take more affirmative action, we are letting the plaintiff’s bar define a false fiduciary liability standard – a standard based on false benchmarks that allows plaintiff lawyers to manufacture fiduciary malpractice claims against any large plan in America.

Disclaimer: The Fid Guru Blog is intended to provide fiduciary thought leadership and advocacy for the plan sponsor community in areas of complex fiduciary litigation. The views expressed on The Fid Guru Blog are exclusively those of the author, and all of the content has been created solely in the author’s individual capacity. It is not affiliated with any other company, and is not intended to represent the views or positions of any policyholder of Euclid Fiduciary, or any insurance company to which Euclid Fiduciary is affiliated. Quotations from this site should credit The Fid Guru Blog. However, this site may not be quoted in any legal brief or any other document to be filed with any Court unless the author has given his written consent in advance. This blog does not intend to provide legal advice. You should consult your own attorney in connection with matters affecting your legal interests.