By Daniel Aronowitz

Key Point

Two federal courts faced with identical investment and fee arrangements reach different results as to whether an excess fee share class claim is plausible. The difference is that the Utah court allowed the plan sponsor to rebut false fee claims with the recordkeeping contract and participant account statements showing revenue sharing rebates, whereas the Minnesota court allowed the same false claims to proceed to discovery.

Since the Supreme Court’s January 2022 decision in Hughes v. Northwestern, the excess fee claim with the most potential to withstand a motion to dismiss is a share-class imprudence claim. A share-class claim asserts that plan fiduciaries acted imprudently by choosing an investment in a retail share class when an identical investment is available to large retirement plans at a lower wholesale price in an institutional share class. But like many excess recordkeeping claims that are based on false and inflated data from the Form 5500, many share-class imprudence claims are also falsely based on incorrect fees. Many of these share-class claims are alleging incorrect fees based on published fee schedules from the investment provider, but many plans have negotiated revenue sharing rebates in which they end up paying less than the retail share class fees, and often less than the institutional share class fees. The actual investment fees being charged – and paid by participants who are serving as named plaintiffs – are easily contradicted by participant account statements and fee disclosures that each of these participants have received four times a year. Plaintiff law firms know their allegations are false, but they assert the false fee claims anyway, alleging misleading issues of fact, knowing that many courts will allow them to proceed to discovery and thus create settlement leverage.

Two cases prove the deception of the excessive fee plaintiffs’ bar. Both the Barrick Gold and the CentraCare purported excessive fee cases involve the: (1) the exact same JP Morgan target-date investments; (2) the exact same fees charged by JP Morgan; (3) the exact same revenue sharing rebates that reduced the fees paid by participants below the lowest-fee institutional share class price; and (4) the respective plaintiff law firms in both cases misrepresented the actual investment fees paid by participants. But there is one critical difference: the District Court of Utah in the Barrick Gold case, which is now on appeal to the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals, allowed the defense to proffer evidence of the recordkeeping contract and the participant account statements to demonstrate that the plan paid less than the institutional share-class fees because of a significant 15 bps revenue sharing rebate back to plan participants. By contrast, the District of Minnesota Court in CentraCare refused to consider the plan participant account statements, fee disclosures, or recordkeeping contract in the context of a motion to dismiss. This evidence proved the identical 15 bps rebate that the Barrick Gold court used to dismiss the complaint, but the Minnesota court ruled that it must allow the claim to proceed even if it is “improbable.” Allowing improbable lawsuits is not the plausibility standard required by the Supreme Court under Hughes v. Northwestern. Consequently, we have two identical cases with false investment fee claims, but one plan sponsor will have to spend millions of dollars to defend itself against false claims – all because two different federal courts apply a different pleading standard on identical facts.

The Barrick Gold Excessive Fee Lawsuit

We previously described the Matney v. Barrick Gold of North America, Inc. purported excess fee case that is on appeal in the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals. ICI Defends Revenue Sharing and Higher-Fee Share Classes in the Tenth Circuit Barrick Gold Case – Euclid Fiduciary (euclidspecialty.com) The excessive fee lawsuit against Barrick Gold was originally filed in 2020 by the prolific Capozzi Adler law firm, who filed over forty of the over 100 excessive fee cases filed in that year. The Barrick Gold 401k plan had 4,858 participants in 2018 with $560m in assets, down from $619m in 2017 because of the 2018 market losses. After the defense filed a motion to dismiss demonstrating that the Barrick Gold lawsuit was a “cut and paste copy of a complaint filed a week earlier” in the Eastern District of North Carolina against Pharmaceutical Product Development, LLC, the Capozzi firm quickly filed an amended complaint. The amended complaint alleged five excessive fee claims that are common parts of the Capozzi excessive fee lawsuit template, including that plan fiduciaries failed to utilize lower-fee share classes. For example, the JP Morgan Smart Retirement R5 target-date funds ranged in fees from .55-.57%, whereas the R6 share class had a lower .44-.47% fee. The difference between the R5 and R6 share classes was ten basis points in most instances.

On April 21, 2022, the Utah District Court granted the motion to dismiss the First Amended Complaint with prejudice, primarily because plaintiffs ignored the 15-basis point revenue sharing credit back to participants. The court rejected plaintiffs’ comparison of the retail-class R5 share class of the JP Morgan TDFs with the lower-fee, but allegedly “identical counterparts” R6 share class. The court held that the comparison to the lower-fee R6 share class was “problematic” because it “relies on incorrect information about actual fees paid by the Plan’s participants.” After the court accounted for the 15-basis-point revenue credit that the plan fiduciaries negotiated for the JPMorgan funds’ R5 share class, the Plan’s expense ratio for each JPMorgan R5 fund was actually less than the R6 funds’ expense ratios upon which Plaintiffs rely. Importantly, the court cites in footnote 11 of the opinion to the Trust Agreement and the 2018 Form 5500 in order to validate that the plan implemented a revenue credit that was not alleged properly in the amended complaint.

The court went outside the complaint to evaluate the actual fees. It did not accept the faulty fee claims by the Capozzi law firm or allow any argument that there is a “factual dispute” that must be litigated in expensive discovery. The court also rejected plaintiffs’ excessive recordkeeping fee claims based on unsuitable comparisons and unsupported speculation that Fidelity did not credit the revenue sharing payments. The court rejected that assertion as implausible given that the amendment in 2017 to the trust agreement required Fidelity to allocate amounts collected from revenue sharing, including that $600,00 to eligible participant accounts. The court did not allow the rank speculation by the plaintiff lawyers to create a false issue of fact – it accepted the documentary evidence from the defense at the pleadings stage.

The CentraCare Excessive Fee Complaint

The Baillon Thome Jozwiak & Wanta LLP law firm filed a purported excessive fee complaint on June 13, 2022 in Schave v. CentraCare Health System in the District Court of Minnesota. The core excess fee claim against the $1.7B plan was that “[s]everal of the plan’s funds were not in the lowest fee share class available to the plan.” It is the exact same share-class claim involving the same JP Morgan SmartRetirement target-date funds and the exact same investment fees as alleged in the Barrick Gold complaint. For example, here is one excerpt from the chart showing five years of the JP Morgan target-date funds with the 10 bps differential between the R5 and R6 share classes:

| Fund in the Plans | Plan Share Class | Expense Ratio | Less Expensive Share Class | Lower Expense Ratio | Excess Cost |

| JPMorgan SmartRetirement 2060 | R5 | 0.62% | R6 | 0.52% | 0.10% |

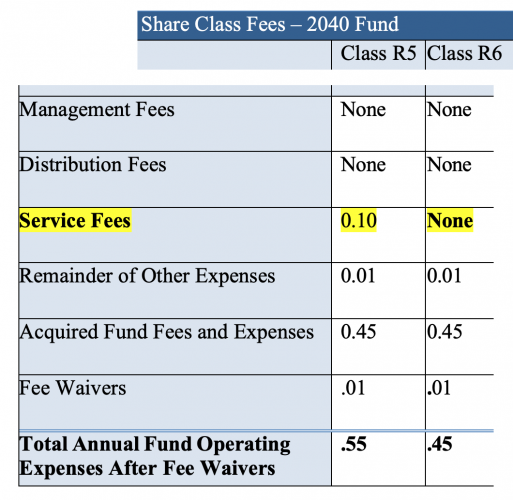

In the memorandum in support of the motion to dismiss the complaint, the Dorsey & Whitney defense lawyers presented evidence that the participant suing in the lawsuit paid less for the R5 share class than the lower fee R6 share class. First, they showed the service fees for the R5 share class of .10%:

The following chart breaks down the fees charged to shareholders in the R5 and R6 shares class as of March 2022 for the 2040 Fund:

Next, they cite from the fund prospectus that states that this .10% Service Fee for the R5 share class could be “shared” – by revenue sharing – with third parties like Fidelity, which, as recordkeeper, coordinated participant communications and provided other services with respect to JPMorgan Funds. The Plans’ Form 5500s disclosed that JPMorgan Funds did exactly that – paying amounts reflecting this Service Fee (and even more) to Fidelity. As a result, JPMorgan paid Fidelity 15 basis points for investment management fees that it received from Schave (the named plaintiff) and other plan participants for the funds in which they invested. Importantly, the Fidelity recordkeeping contract reveals that Fidelity agreed that, after receiving the 15 basis points from JPMorgan Funds for each of the Plans’ investments, it would rebate to the Plans the full amount of that payment. Furthermore, the rebate is reflected on Schave’s 401k Account statements, which notes a corresponding credit to her individual account. Therefore, as a result of Fidelity’s rebate of the JPMorgan revenue share, the amount that the Plans pays for the R5 share class of the JPMorgan Funds was effectively reduced by 15 basis points. Although the R5 share class’s publicly posted expense ratio is higher than that of the R6 share class, the Plans effectively paid less for the R5 shares than they would have for the R6 shares that had no Service Fee.

The motion to dismiss then cited the Barrick Gold decision because the facts are “indistinguishable”:

Citing this exact rationale with respect to the same Fidelity recordkeeper rebate arrangement, another district court has, in fact, dismissed an indistinguishable 401(k) fee class action lawsuit. In Matney v. Barrick Gold, Plaintiffs alleged, as here, that plan fiduciaries imprudently offered the R5 shares of JPMorgan target date funds, which cost more than those of the R6 class that was available. The court reviewed, as embraced by the pleadings, Fidelity’s recordkeeping arrangement which “show[ed] the expense ratios are actually lower,” as a result of Fidelity’s agreement to pay to the plans any revenue sharing that is received from JP Morgan. “Taking into account the 15-basis-point revenue credit that Defendants negotiated for the JPMorgan funds R5 share class,” the Court observed “the Plan’s expense ratio for each JPMorgan R5 fund was actually less than the R6 funds’ expense ratios upon which Plaintiffs reply.”

On January 27, 2023, the United State District Court of Minnesota issued its decision on the motion to dismiss. It dismissed the investment fees and performance claims that purport to compare the fifteen active investments to passive comparators, but the court allowed the share-class claims to proceed to discovery. The court took the plaintiff’s allegation at face value that “there allegedly ‘is no difference between share classes other than cost – the funds hold identical investments and have the same manager.’” According to plaintiff, although the CentraCare plans qualified for a less expensive R6 institutional share class, they instead chose a higher-cost R5 share class without receiving any additional benefits for plan participants. The court reasoned that these claims are materially analogous to the Braden v. Wal-Mart Stores and Davis v. Washington University in St. Louis, and thus support a plausible inference that defendants breached their fiduciary duties under ERISA. The court acknowledged that the defense had argued that the plans negotiated rebates which offset the cost difference. But the court held that “[w]hen an ERISA plaintiff’s allegations support a plausible inference of mismanagement, dismissal is not warranted merely because the defendant has identified an alternative plausible inference.” The court cited to the Davis v. Washington University case that a “well-pleaded complaint may proceed even if it strikes a savvy judge that actual proof of those facts is improbable, and that recovery is very remote and unlikely.” Mysteriously, the court never mentions that another federal court in the Barrick Gold case, albeit in another circuit, had dismissed a complaint based on identical facts and evidence.

Simply put, the CentraCare court allowed an excess fee case to proceed that is based on a misrepresented level of fees. There is no credible dispute. The evidence that Fidelity rebated 15 basis points is not merely “an alternative plausible inference.” It is the truth – and the plaintiff law firms knows it. The plan did not pay the investment fees alleged in the complaint. But the court turned a blind eye to the truth and allowed what it conceded might be an improbable case to proceed.

The Euclid Perspective

The CentraCare decision allowing a fake share class excess fee claim to proceed is wrong on many levels. First, plan fiduciaries deserve to know upfront what their fiduciary responsibilities are. They deserve to know whether the use of revenue sharing rebates meets fiduciary liability standards. Second, they deserve a predictable and uniform liability standard. They should not be subject to a capricious liability trap in which they are at the mercy of what judge gets assigned for their case, or where a case is filed. Third, courts must apply the same, uniform pleading standard in all ERISA cases. It is not fair when some courts allow consideration of participant account statements, but others do not. These participant statements are reliable evidence of the recordkeeping and investments fees paid by plan participants. Finally, a uniform pleading and liability standard is necessary to stop fake fiduciary malpractice claims. Plaintiff lawyers are officers of the judicial system and must be held accountable for filing false fee claims.

Let us be clear: it is one thing to argue that the fees charged by JP Morgan are too high. Both lawsuits attempt to compare actively managed fees against passively managed fees. Most courts now find this comparison to be implausible. And unlike the CentraCare case, which only compares active to passive investment fees, the Barrick Gold complaint at least attempts to compare JP Morgan actively managed fees against another actively managed target-date funds offered by American Funds. We are not agreeing with the analysis, but a comparison of active-to-active investments is a potentially legitimate claim if the investments are truly comparable. Our objection is to a complaint that seeks serious liability for fiduciary malpractice based on false fee amounts. Plaintiff lawyers are asserting that false fee amounts are too high. That is intentionally dishonest. There may be a legitimate claim that the JP Morgan fees are unjustifiably higher than what Fidelity, Vanguard, American Funds, or State Street charge for comparable products with similar actively managed strategies. But these share class cases go too far in deliberately asserting excessive fees based on a fee amount that is incorrect and easily rebutted by government-mandated fee disclosures and account statements.

Unfortunately, this type of fake share-class claim is not an isolated circumstance. For example, the Wenzel Fenton Cabassa, P.A. law firm filed a purported excess fee lawsuit in Davis v. Old Dominion Freight Line, Inc. on November 18, 2022 in the Middle District of North Carolina. The facts are the same as the Barrick Gold and CentraCare lawsuits, alleging that the plan fiduciaries are guilty of fiduciary imprudence for choosing – you guessed it – the R5 share class of the JPMorgan Smart Retirement target date funds when the R6 share class was available for 10 basis points cheaper. The Wenzel law firm makes no effort in their complaint to meet any duty of candor to provide participant account statements or fee disclosures provided to their sole client who was a participant in the plan. The complaint is based on published fee schedules, not the actual fees charged to their client. It is like going to Whole Foods and claiming that the price for organic milk is too high, but not disclosing that you got a discount for being a Prime member or using a coupon. Why are they hiding the true fees charged to their client? Because it would sink their case, which relies on misleading the court, and hoping that the assigned judge will not allow any true evidence of the actual fees paid at the pleadings stage.

It is time for the Department of Labor to intervene to stop these false fee claims, or for courts to apply a uniform pleadings standard that is based on the truth. Anything less is acknowledging that the judicial system is allowing plaintiff law firms to profit off misrepresentations.